In October 2023, I had the pleasure of presenting a paper at the North American Division’s Women in Adventist History Conference. My paper, “The Invisible Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps: Women in a Man’s World,” briefly explored the lives of four women who at one time or another were involved in the Medical Cadet Corps between 1938 and 1958. Limited to only twenty minutes in which to speak, my research retrieved far more material than I had time to share then. Thus, it is my privilege in this article and in the coming months to more fully explore the lives and contributions of these four women in addition to two more women who should have been included in the original presentation.

When the first Union College Medical Corps was organized in January 1934, no one thought about women becoming involved in a significant way. The junior and senior young ladies of Union College, wanting to support their male classmates, organized a mission fundraiser in which they sewed red cross armbands to sell to the men for their uniforms during the December 1934 Week of Sacrifice—a week where every student found ways to pledge money to Adventist mission work. The proceeds were donated to Adventist missions. This peripheral role was acceptable, but in 1934 it was hard to imagine a scenario where women would teach or be instructed in what was to become the Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps (MCC).

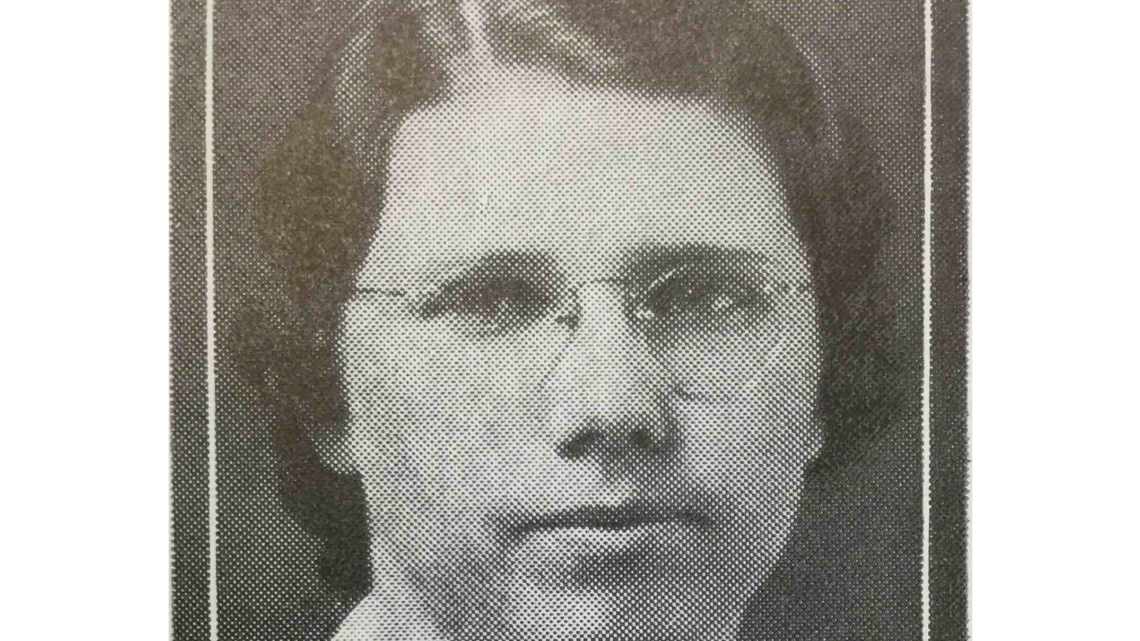

The first woman known to have served as an instructor in the all-male MCC did not come from Union College. Dr. Verna Lucille Robson was actually a graduate of Pacific Union College and the College of Medical Evangelists. And she did not teach at Union College. Emmanuel Missionary College (EMC) in Berrien Springs, Michigan, hired her fresh out of medical school. She began work at EMC in the autumn of 1937, the same semester the college started discussing the idea of piloting a Medical Cadet Corps Course.

Born on September 17, 1911, in Highland, California, to Christopher and Effie Robson, Verna was one of six children. Although she attended elementary and high school in San Bernardino, California, and was baptized in the Loma Linda University Church, she studied pre-medicine at Pacific Union College. After graduation from PUC in 1934, she returned to Southern California to study medicine at the College of Medical Evangelists (CME). As part of her medical studies, she took an internship with Boulder Sanitarium in Colorado in 1936-1937. Thus, she was a newly graduated medical doctor when Emmanuel Missionary College (EMC) invited her to become college physician and instructor of biological science in 1937 with a salary of $27 per week.

EMC faculty decided to organize the MCC on a trial basis in January 1938, enrolling only one hundred young men. Verna Robson, along with a Dr. Garrett, was appointed medical instructor of this trial project. Ultimately, only sixty young men registered for the first semester of training, and eighty for the second semester. However, this one, or possibly two, years of involvement with the MCC is a forgotten footnote in both Robson’s career and the history of the MCC.

Expectations for fifty-two-hour work weeks at EMC took a toll on Robson’s health. She was granted $100 toward graduate study at CME in the summer of 1938, and that autumn her wages were increased to $29 per week, retroactive to June 19, 1938. This was to bring her wages up to the General Conference pay scale for physicians. However, in the spring of 1939, Robson suffered an unspecified health crisis which put her in the Pine Crest Sanitorium in Oshtemo, Michigan. One can only surmise that this crisis was precipitated by working fifty-two hours a week.

After two years as EMC campus physician, the school yearbook concluded “the Doctor has quietly and efficiently served E. M. C. as our physician. Her approachable reserve has won for her a large circle of friends.” There was no mention of her contribution to the MCC. She resigned from EMC effective January 1, 1940, having accepted a position at the Pine Crest Sanitorium where she pursued “her interests in specialized medicine.”

Robson’s career after she left EMC is actually much more interesting. After several years in Michigan, she returned to California where she worked with tuberculosis patients in the San Fernando Valley for a short time. This was followed by seven years at the Saint Helena Sanitarium. Robson later moved to Grants Pass, Oregon, where she worked in private practice. She was the first female physician in this town. In 1946, she served on the General Conference’s Medical Advisory Board.

In September 1954 Robson accepted a call to Karachi, Pakistan. Arriving on January 4, 1955, she worked at the Karachi Seventh-day Adventist Hospital until 1958. She was one of three physicians on staff who served 39,000 patients in 1955 alone. During her time in Pakistan, she visited the Hunza Valley while on vacation with a group of hospital staff.

Robson permanently returned to the United States from Pakistan in 1960. Inspired by the many cases she treated in Pakistan that could have been prevented by proper public health measures, she enrolled at the University of California–Berkeley, and earned a degree in public health. She accepted a position in Sacramento County’s public health department where she held a variety of positions from 1961 to 1972 including tuberculosis control officer and chief of the infectious and communicable disease control program. Under her leadership, cases of tuberculosis in Sacramento County were reduced by four-fifths.

The coda to this illustrious career is that after she retired in 1972, Robson married for the first time in 1982 at the age of seventy. Marriage must have agreed with her, because after the death of her first husband, Harold Towsley (1911-1993)—an old boyfriend from undergraduate PUC days—she remarried. Her second husband, Vando Unger (1909-2006), was just a few days shy of his ninetieth birthday at their wedding. She outlived him by seven years, dying on August 24, 2013, just twenty-four days short of her 102nd birthday.