I have never before felt the need to start a story with a disclaimer. However, the story that follows is disturbing. I have chosen to share it, not for the salacious details, but rather to provoke thoughtfulness. Thoughtfulness about the trauma people around us may be experiencing. Thoughtfulness about the bias of social norms. Thoughtfulness about accepting stories at face value. These are serious issues for which there is no pat or trite answer. Yes, prayer is always good. Yes, marriage is a sacred bond. But neither belief negates the need for professional intervention, for measures to protect personal safety, nor for a definition of marriage that requires equal and mutual respect on the part of both spouses.

Obsession

Enthusiasts of Adventist church history will remember the name B. F. Snook. He was the early Adventist minister in Iowa who co-led the Marion Party, an early splinter group. Ultimately, Snook and his entire family left Adventism. While B. F. Snook became a Universalist minister and lecturer of some renown, his second son, Arthur L., born in 1860 in Marion, Iowa—and who may have studied law and been well-to-do at one point—eventually became a poor brakeman on the Missouri Pacific railway line between Kansas City and Nevada, Missouri, near the time the story that follows took place. The first hole in this story is Arthur’s employment history and the state of his mental health.

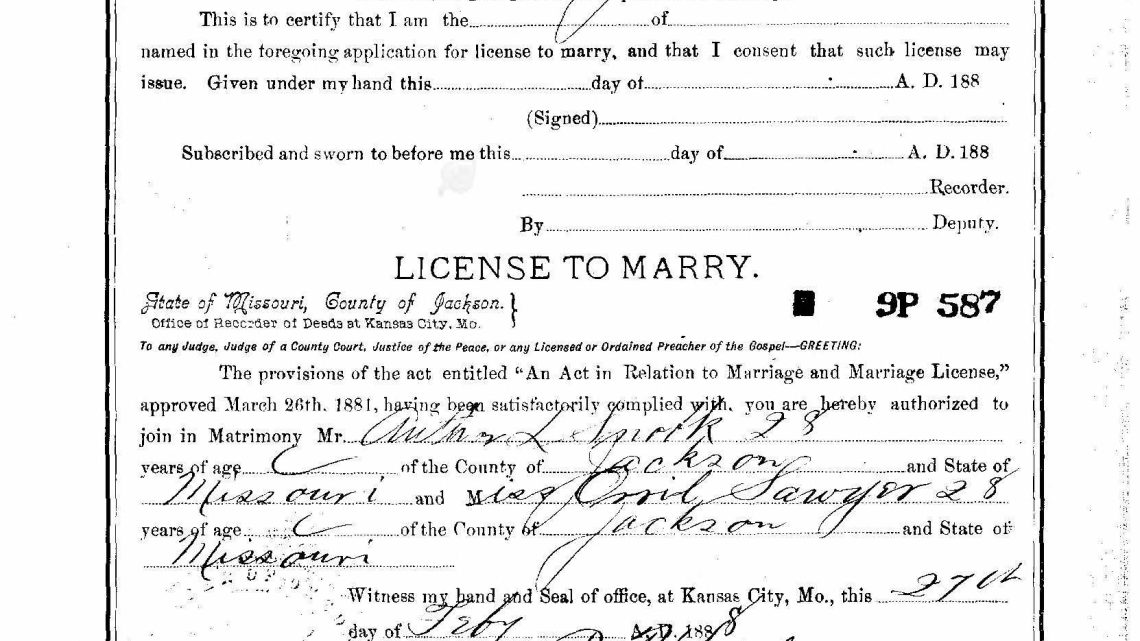

On February 27, 1888, in Kansas City, Missouri, Arthur married a onetime resident of Bedford, Iowa. Her name is not spelled the same way twice in any of the available documents. The variations include O. A., Oral, Orill, Orril, Orrel, Oletta, and Arletta. We know her father was Henry Sawyer, so for clarity, let’s call her Ms. Sawyer. At the time of her marriage to Arthur, Ms. Sawyer was the divorced mother of a ten-year-old daughter named Myrtle, who lived with her mother and new step-father. For unspecified—but likely economic—reasons, Ms. Sawyer became unhappy with her husband. She was criticized for desiring to live in Kansas City rather than with him in Nevada, Missouri, and for maintaining her own career as a canvassing agent for a publishing house (non-Adventist). Labeled unfaithful, no other evidence was provided. While Arthur loved her “with a devotion that was really an insanity,” she “squandered” his income, “keeping him impoverished.”

The situation came to a head the night of November 3, 1896. Ms. Sawyer and Myrtle were living at “the Gibson house”—either a hotel or a boarding house—where Arthur found her and pleaded his case one more time. She allowed him into her room for the night, where they argued long and loud. Ms. Sawyer’s reported swearing during the altercation was another strike against her. The following morning in an apparent attempt to protect Ms. Sawyer, the Gibson House’s proprietress forbade Arthur from entering the building. He then sent his wife a note asking her to meet him down the street at the Belmont Hotel. Shortly after noon in the full view of witnesses, she complied, meeting him at the hotel entrance where he shot her in the head and then proceeded to commit suicide, shooting himself in the chest.

Reflection

The entire record of these events were reported through a masculine lens. The newspaper reporters were men. The witnesses they quoted were men. The husband received all of the sympathy, and the wife all of the condemnation. The marginally sympathetic Kansas City Star noted that Arthur appeared drunk to some witnesses. However, in Iowa, the newspapers reported that Arthur “had been reared with all the instincts of a fine Christian family” and that “he was universally esteemed,” “respected and loved by everyone that knew him.” The implication was that Arthur had the right to expect a wife who would stay at home, keep house, and let him control his money. However, one need only read between the lines to see an alternate narrative.

Arthur had apparently lost a considerable amount of money. Exactly how that happened is another hole in the story. He suffered an injury working for the railroad, which resulted in the loss of a foot. This could have been the catalyst for their reduced circumstances. Did the pain of his injury lead to substance abuse? That is another hole in the story. One can easily imagine Ms. Sawyer wanting to improve the family’s financial stability by taking work outside the home. In fact, if Arthur had become unstable, she may have felt the need to take total control of their income to ensure the family’s security. Thus, the accusation that she “impoverished” him, perhaps to prevent him from squandering the money himself. And finally, her work may have required that she stay in Kansas City. The true version of the story may never be known—holes in the story—but imagining an alternative narrative is a step toward empathy. Toward understanding why an individual has made or is making the choices they are.

In support of his granddaughter, Ms. Sawyer’s first father-in-law, Leonard Turley McCoun, claimed her body, taking it back to Bedford, Iowa, for burial. McCoun was a pioneer of Taylor County, Iowa. A well-known attorney, he was a veteran of both the Mexican and Civil wars, and widely respected. He was quoted as saying, “We all loved Mr. Snook. We knew her and knew her to be unworthy of him. She led my son [her first husband] a life of misery and wretchedness until he left her and she is the source of Arthur Snook’s death.” A very harsh assessment of the woman who was not holding the gun. How does the perception of unfulfilled wifely duty negate the offended husband’s responsibility for his own actions?

Left in the hands of her more powerful and influential father-in-law, Ms. Sawyer’s reputation had not a chance. At least not until thirteen months later when McCoun had a good reason to reassess his view of his own son. But that is a story for another day. Lest the reader think that the author has wandered too far from the path of Adventist history, stay tuned. The connection is coming in Part 2.