Arthur Dent, the protagonist in “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” said, “You know, I’ve always felt there is something fundamentally wrong with the Universe.” One of the reasons I am a Seventh-day Adventist and would recommend it to anyone who feels like Arthur Dent, is that Adventism provides the best answer to the simple question, “What is wrong with the universe?” Or, put another way, “Why does the universe make no sense?”

And where better to seek that answer than in the story of the earliest person to ask that question, the earliest person to realize that the universe we live in doesn’t seem to make sense? The first hitchhiker.

All of us believe in an intuitive way, that if we play by the rules, we do the right things, we help our fellow man, and so on, that we will be rewarded with a long and prosperous life. We also believe that those who do the wrong things, who hurt their fellow men, and so on, will suffer and be punished. I mean, we think that’s the way things are supposed to be. Except for one thing: they are not.

One of the oldest stories in the Bible is one that explores that problem: the story of Job. According to one scholar, Robert Alter, Job is “in several ways the most mysterious book of the Hebrew Bible.”* The book begins with a startlingly positive testimony:

There was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job;and that man was blameless, upright, fearing God and turning away from evil.

The text goes on to confirm that Job’s situation matches our basic assumption: he is rich in every sense of the word. He has many children — who, as we shall see, all get along, even in adulthood — he has great wealth, and his men a spotless reputation. He does the right things, and he has been appropriately rewarded. Not only that, but the text tells us that he prays for his children every day. He is a man of caring and devotion.

But then, in one day, disaster strikes him. One after another, sole-surviving servant-messengers arrive with news that all of his wealth, as reckoned in animals and servants, has been progressively destroyed. He suffers multiple shocks; the narrative makes it clear that no sooner has the first messenger brought news of disaster on one front, another one comes with news of yet another disaster. And finally, a servant comes with the most dreaded news of all: his children had all been gathered in the home of his eldest son for a feast, and suddenly a whirlwind had come destroying the house and killing all of its inhabitants.

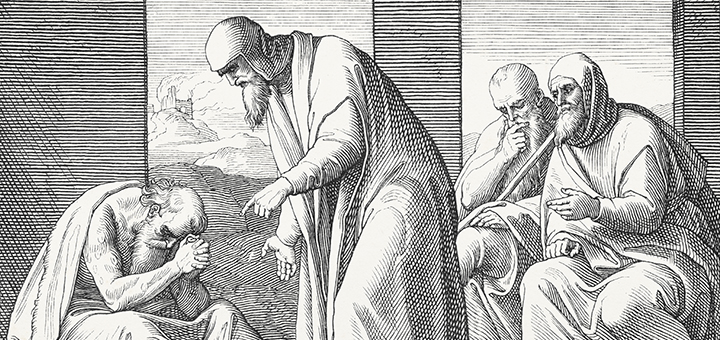

Job is beside himself with grief — who wouldn’t be? His own wife, no doubt in grief and shock herself, tells him to give it up, to curse God, and die. And before long, three of his friends come to be with him, but their presence is not an unmixed blessing.

Each of these friends, in turn, insist on reinforcing that basic worldview we all share. Since good life and good deeds are rewarded with wealth and prosperity and good things, and evil deeds are rewarded with punishment, clearly someone had done wrong. All of his friends agree on that. They only disagree on who did the wrong, and whether the punishment was really that severe.

Eliphaz says to Job, in essence, “Its your fault.” A full-fledged apostle of conventional wisdom, he says in effect, “Good people don’t have bad things happen to them. But those who do evil receive punishment.” And then, he adds a bitter pill: “be thankful when God corrects you.”

Job is in deep grief and probably still in shock. He has lost everything, even his children, and now Eliphaz thinks that Job should be thankful for these disasters. We all too often use the expression, “the patience of Job,” without thinking what that really means. In my view, the fact that Job didn’t rise up and murder Eliphaz on the spot is an indication of his patience.

Bildad, demonstrating that piling on was not invented by the NFL, goes further. He tells Job that God never makes mistakes, so if Job lost all of his wealth, it’s because he deserved it. And to make matters worse, he says that since Job’s children were destroyed, they must also have done wrong. Not only does this spread the guilt from Job to his children, it also tells Job that his prayers for his children went unanswered. Now that is piling on.

Not to be outdone, and in the wonderful Hebrew poetic tradition of repeating a theme and escalating each time, Zophar goes his two friends one better. He tells Job, in effect, “You didn’t get half of what you deserve.”

But Job knows better. He does not claim perfection, he simply claims that he has done nothing recently that was any different than he has always been doing. No doubt, in times of prosperity, these same three friends praised Job for his upright behavior. But now that calamity has befallen him they assume it is his fault. And there it is.

Suddenly, for Job, there seems to be something fundamentally wrong with the universe. Just like for Arthur Dent, things don’t add up. That’s why his friends insist that he has done something wrong. They want the universe to make sense; they want things to add up. They do not yet recognize the reality that Job and Arthur Dent have collided with.

It’s easy for us to be critical of Job’s three friends. But many of us share the same mistaken worldview. Many of us secretly believe, in our heart of hearts, that if we eat right and exercise right, we will be blessed with good health and long life. That is the universe of our wishes. But that is not the universe in which we live. Sometimes, people who are selfish, who eat whatever they please, smoke and drink and indulge all of their appetites live long and apparently healthy lives. And sometimes those who are the most health-conscious die young.

I could go on and on, but you know what I’m talking about. Surely, if we read the Bible every day, we will be saved. Surely that’s good enough to get us into heaven. The story of Job warns us against these glib and easy verdicts. But there is so much more to it. We all have these little rituals, these closet superstitions that we think will protect us. And just like Job’s friends, when these superstitions run into contrary evidence, in our eagerness to preserve our fantasy world, we can be extraordinarily cruel.

So how can all this be? How can we both harbor these pleasant notions about goodness and reward, about badness in punishment, and yet see that the opposite happens all around us? And why does it happen? The story of Job answers that, too. And the way it answers those questions provides a clue to a distinctive Adventist belief. What that belief is, some of you already know. What you may not have thought of, though, is how the book of Job functions with relation to the rest of the Bible.

Read other posts from this series on Adventist Identity.

[hr]

*(2010-10-11). The Wisdom Books: Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes: A Translation with Commentary (Kindle Locations 250-251). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.