“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” Those famous words begin Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, foreshadowing the tale of stark contrasts. For in it, a most frivolous man makes the most profound sacrifice. A subject of the greatest empire on earth will die at the hands of a mob in the most corrupt of cities. A noble character from a corrupt society will be saved by an erstwhile scoundrel from an affluent society. All this in the context of the French Revolution, one of the darkest chapters of Earth’s history.

Dickens might have been describing the story of Ruth, though for quite different reasons. The contrasts are as stark, for though no actual violence occurs there is death and bitterness. In fact, life and death launch the story. But for the observant reader, the Ruth narrative contains layer after layer of irony and reversal, as in Dickens’ great story. The drama is intense in Ruth, but always subdued.

There are differences of course. A Tale of Two Cities rewards even the most casual reader with its conflict and drama. Only the truly attentive can savor the delights of Ruth.

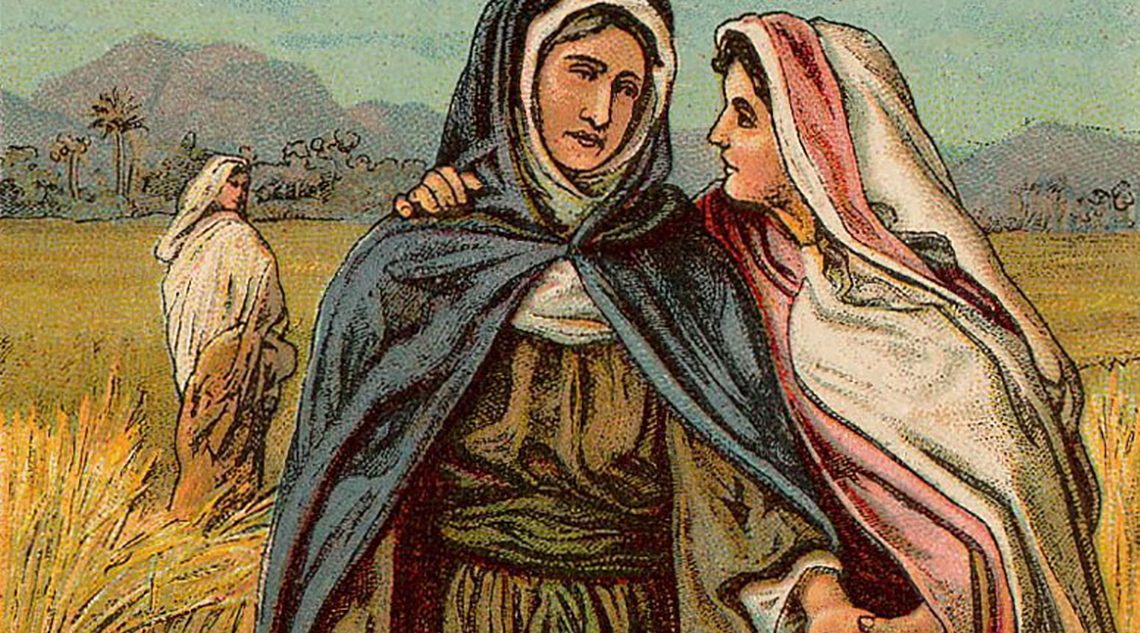

On its surface, Ruth is a charming romance. A famine leaves three women, two of them daughters-in-law of the third, widowed. Bereaved and bitter—she even says her new name is “Mara” (bitter)—the older woman determines to return to the land of her birth, and die there. She encourages the younger women to remain where they are, where the prospects of finding a husband will be better. One daughter-in-law agrees, but the other one, intensely loyal, vows to stay with the older woman, and die in the—to her—foreign land. After a series of adventures, the plucky young widow finds a husband, and provides a legacy for her mother-in-law. That’s the romance. But even as a romance, that just scratches the surface.

As you may remember, in the story of Jochebed and Moses we encountered the Betrothal Narrative story framework. On the surface, the entire book of Ruth is a Betrothal Narrative, but with many twists and turns. We’ve also looked at The Barren Woman and The Rejected Cornerstone. They show up in the story of Ruth as well. In fact, the story of Ruth is so intricately crafted that we will encounter all these and yet two more story frameworks: The Sojourner, and The Firstborn Reversal. The author combines all of these and more into an incredibly rich narrative tapestry. They will emerge as we dig under the surface of the story.

In the days when the judges judged, there was a famine in the land. A certain man of Bethlehem Judah went to live in the country of Moab, he, and his wife, and his two sons. The name of the man was Elimelech, and the name of his wife Naomi. The names of his two sons were Mahlon and Chilion, Ephrathites of Bethlehem Judah. They came into the country of Moab, and lived there.

This in itself is a familiar story. Famine drove Jacob and his sons to Egypt. They were saved from famine, but ended up enslaved, so their exile had both good and bad. Famine drives Elimelech and his family to Moab. But their exile appears only to have bad results.

Elimelech, Naomi’s husband, died; and she was left with her two sons. They took for themselves wives of the women of Moab. The name of the one was Orpah, and the name of the other was Ruth. They lived there about ten years. Mahlon and Chilion both died, and the woman was bereaved of her two children and of her husband.

And here we see the first hint of the many ironies and twists this story has in store for us. Naomi has become, late in life, a barren woman. For the ancient reader this is ironic beyond words. Israelites were forbidden to intermarry with foreigners, but especially those from Moab. It was the Moabites who summoned Balaam to curse the Israelites and, when he failed to do so, counseled the Moabites to seduce the Israelites into immorality. The Moabites worshiped a fertility god, Chemosh, which took the form both of ritual prostitution and infant sacrifice, both of which were abominations to Israel’s God. Further, the Moabites were tainted from the beginning, since Moab, for whom the nation was named, was the fruit of the incestuous union of Lot and his daughters after the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.

The lesson is painfully clear. Naomi moves with her husband and sons into a land where fertility is worshiped and licentious behavior is common, and there she becomes barren. She has a husband and two sons when she moves to Moab, but loses them all there. Naomi gets the point, as she makes clear when she and her daughters-in-law approach the land of Israel:

Naomi said, “Go back, my daughters. Why do you want to go with me? Do I still have sons in my womb, that they may be your husbands?

Go back, my daughters, go your way; for I am too old to have a husband. If I should say, ‘I have hope,’ if I should even have a husband tonight, and should also bear sons; would you then wait until they were grown?

Would you then refrain from having husbands? No, my daughters, for it grieves me seriously for your sakes, for Yahweh’s hand has gone out against me.”

Naomi thus declares herself barren at God’s hands. She has no sons to offer, nor is it possible that she will at some later date, and even if she did, it would be too long before they could grow to manhood. She is destitute.

“God is punishing me,” Naomi tells them. “No reason for you to suffer, too.” And she knows, even if she does not say it, that Moabite women may not be properly respected in Israel. Despite her protestations, Ruth makes clear her determination to stay with Naomi—an especially amazing promise because Naomi herself is deeply unhappy.