Desmond Doss’s name is synonymous with the heroic image of self-sacrificing non-combatant medics. But he was far from the only Adventist non-combatant soldier deserving of recognition. Doss was fortunate to survive to tell his story and receive recognition. Aaron Oswald was not so fortunate.

Union College Medical Corps

Born May 21, 1914, in Campbell County, South Dakota, Aaron Emil Oswald was the son of Emil H. Oswald (1886-1960) and his wife, Helen Kielbauch (1889-1984). An Adventist minister, E. H. Oswald at various times served as president of the South Dakota, Wisconsin, North Dakota, Minnesota, Wyoming, and Alberta conferences as well as the Northern Union Conference. While a student, Aaron Oswald spent his summers serving as a tent master for meetings in his father’s conferences.

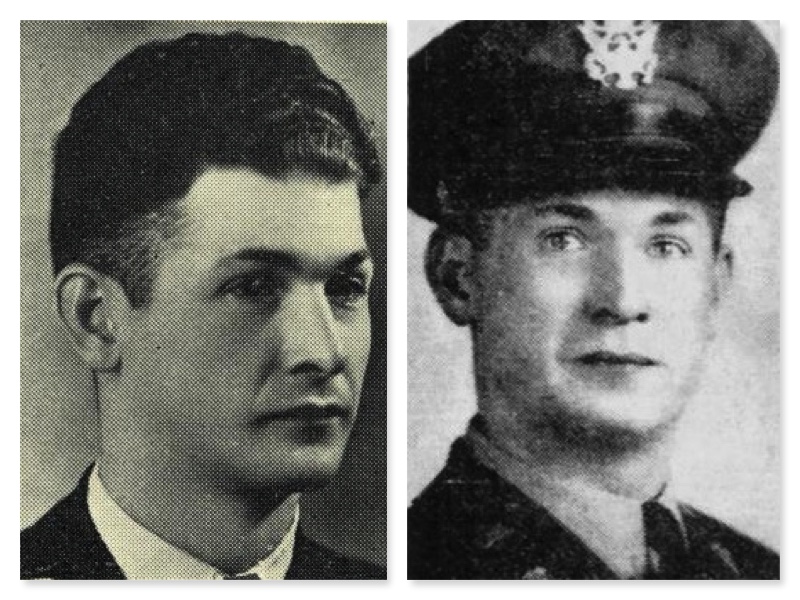

Aaron Oswald graduated from Bethel Academy in Wisconsin before enrolling at Union College as a pre-med student. His younger sister, Miriam, accompanied him to Lincoln, enrolling in Union College Academy courses. When Union College announced the first Medical Corps class to begin January 8, 1934, offering military medical training for young men of draft age, Oswald was in line. During the Medical Corps’ second term, he was promoted to lieutenant in November 1934. Thus, he numbered among a select group of student officers, many of whom would become officers and instructors of the Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps at Adventist college and academy campuses over the next three decades.

College of Medical Evangelists

In the fall of 1935, Oswald began medical school at the College of Medical Evangelists (now Loma Linda University). As a freshman medical student, he was elected president of his class. During his internship at St. Luke’s Hospital in Denver, Colorado, he registered for the draft in October 1940. Upon graduation from medical school, he began work at Methodist Hospital in Los Angeles. Oswald transferred to the Kern County General Hospital in Bakersfield, California, in October 1941. Whether Oswald was drafted or volunteered for service is unknown. Regardless, his education qualified him for an officer’s commission which he accepted in the spring of 1942. Before he shipped out to the Pacific Theater, he married a nurse, DeLora B. Smith, on August 7, 1942.

Life in the Army

In the spring of 1942, Oswald accepted an officer’s commission in the Army Medical Corps. He was made a flight surgeon and assigned to the 72nd Bomb Squadron of the 5th Bombardment Group. This bomber group departed Hawaii in November 1942 with the objective to surveil and attack Japanese installations in the Solomon Islands. Its early missions supported the campaign for Guadalcanal. Between August 1943 and the spring of 1944, the group participated in the campaigns against Bougainville, New Britain, and New Ireland. In April and May 1944, it attacked Woleai, and between June and August 1944 it operated over the islands of Truk and Palau. It briefly attacked targets in the Dutch East Indies and on Borneo before turning its effort toward the Philippines. Beginning in October 1944, the group’s missions supported infantry invading the Philippines. Near the end of 1944, it was part of the 61,000 service personnel who arrived on Morotai Island.

Without access to Oswald’s service record, his precise movements and actions are not completely known. However, two citations “for valor and bravery” provide an idea of the integrity and commitment he gave his task. While in the Admiralty Islands in the first half of 1944, he “voluntarily and at great risk to his life entered the burning wreckage of a crashed heavy bombardment airplane and rescued a disabled gunner.” For this courageous action, in June 1944 he received the Soldier’s Medal—the highest honor reserved for soldiers who risk their lives in non-combat situations. His participation in aerial flights over the Southwest Pacific from January 5, 1944, to October 3, 1944, resulted in a meritorious achievement award.

Oswald was a popular officer. One of his fellow physicians wrote of him:

Dr. Oswald was the best-liked flight surgeon of his group. He commanded the respect and admiration of his fellow officers and men for himself and for his religion. He had recently prepared a series of studies, and each Sabbath that the Adventists gathered together it was usually he who led out in the meetings.

For his part, Oswald desired to “help to keep my boys partially contented and in good health.” If successful he believed “that is some recompense.” He did not confine his medical services to the airmen under his care, but also provided what treatment he could to the islanders he encountered. This gave him a taste for medical missionary work. He wrote his wife:

Diseases are rampant among them. I saw not a few of them disfigured by leprosy. I came back deeply impressed with the needs of these people for a medical missionary. I could not think of a more satisfying work than to bring relief to these suffering, ignorant, superstitious natives. Their gratitude would be the greatest compensation that any doctor could desire. I can’t account for the strong impression I’ve had the past three months or so to be a medical missionary unless it is divine guidance. I know that God has led in my life very definitely through all these years, and I wouldn’t want to refuse His desires for me now.

Laying Down His Life

As loaded bombers took off from Morotai Island on Sabbath, February 24, 1945, destined for enemy targets, one pilot crashed. His aircraft on fire, Oswald ran to the rescue. By some accounts he dragged the pilot twenty-five feet from the burning aircraft. Other accounts claim he made it fifty feet before the bombs exploded. Shrapnel killed Oswald immediately. The pilot he tried to rescue, died the next day.

Following a funeral, Oswald was buried in the United States Army cemetery in the Morotai Islands. In the United States, memorial services were held at the White Memorial Church in Los Angeles and the Casper Church in Wyoming where his parents resided. In early 1949, Aaron Oswald’s remains were returned to the United States and placed in the Golden Gate Memorial National Cemetery in San Bruno, California.

Mostly forgotten now, Oswald’s classmates endeavored to keep his memory alive. In 1949, Union College students dedicated the 49ers Field, the outdoor athletic facilities at the time, to alumni who fell in World War II. Aaron Oswald’s name was among those engraved on the base of the flagpole. In 1954, the Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps also established the Aaron E. Oswald Medal of Merit to be given to cadets “who demonstrate leadership and service above the line of duty” (“The Aaron E. Oswald Medal of Merit,” Southern Tidings 48, no. 19 (May 12, 1954): 9–10). Oswald did not live to become a leader in the MCC as did his classmates, but they were responsible for preserving his legacy through the Medal of Merit. His story was frequently retold whenever and wherever the award was presented.

*Unless otherwise noted, quotations through this article are taken from Arthur L. Bietz, “In Commemoration of Captain Aaron E. Oswald,” Northern Union Outlook, April 3, 1945, 4-5.