Times are desperate in Israel. There are endless border skirmishes with the Philistines. The priests have become corrupt and are extorting worshipers to bring sacrifices, including sexual favors from women[See 1 Samuel 2:22.]. The high priest, Eli, is unable to control his sons. Israel is in desperate straits.

The rot in Israel runs deep, but there are places which on the surface seem peaceful, where the conflict is personal rather than national. Our story transpires in one of these places. It begins with one woman’s anguish.

Now there was a certain man . . . and his name was Elkanah , . . . an Ephraimite.

He had two wives. The name of one was Hannah, and the name of other Peninnah. Peninnah had children, but Hannah had no children.

“Hannah had no children.” We have seen this situation before in scripture. Two wives, one has children, the other does not. In a culture where fertility is the basis of wealth, the childless woman feels herself without worth.

This man went up out of his city from year to year to worship and to sacrifice to Yahweh of Armies in Shiloh. The two sons of Eli, Hophni and Phinehas, priests to Yahweh, were there.

When the day came that Elkanah sacrificed, he gave to Peninnah his wife, and to all her sons and her daughters, portions; but to Hannah he gave a double portion, for he loved Hannah, but Yahweh had shut up her womb.

Another complicating factor: as so often happens, the wife without children is more loved by the husband. “To Hannah he gave a double portion.” By now, you recognize that this “double portion” is the one belonging to the firstborn. In his man’s way, Elkanah tries to make up to Hannah for her barrenness. But it has the opposite effect. For Hannah, it emphasizes what she sees as her failure; it infuriates Penninah, who reckons herself as undervalued, and Hannah as the cause.

Her rival provoked her severely, to irritate her, because Yahweh had shut up her womb. As he did so year by year, when she went up to Yahweh’s house. Her rival provoked her; therefore she wept, and didn’t eat.

This, too, we have seen before. The fertile wife seeing the affection her husband displays for ‘that other woman,’ experiences jealousy and pain, which she tries to mitigate by taking it out on her sister wife. We saw that with Hagar and Sarah, with Leah and Rachel—which will become relevant in our story presently—and now we see it with Penninah and Hannah. Of course Penninah does not do this openly, where Elkanah would be angered. And Elkanah, for his part, does not realize his demonstration of preference only makes matters worse.

An outside observer immediately understands Hannah’s dread of the annual pilgrimage to make sacrifice. But Elkanah, oblivious to all this, and specifically to how his actions exacerbate the situation, cannot understand. He must be thinking, “What is wrong with this woman?!”

Elkanah her husband said to her, “Hannah, why do you weep? Why don’t you eat? Why is your heart grieved? Am I not better to you than ten sons?”

Why does he say “ten sons?” One would expect seven, the number of perfection, of completion. That’s why the women of Behtlehem declared to Naomi that Ruth “your daughter-in-law, who loves you, . . . is better to you than seven sons.” Ruth, they said was better than the perfect son. It seems natural that Elkanah would say the same, am I not better to you than ‘the perfect son.’ But he pointedly says ten. Why?

We have already identified Elkanah as “an Ephraimite.” In Israel, tribal identity matters. There were twelve tribes, however, no ten? So once again, why ten instead of twelve? Had we not already thought of Leah and Rachel, Elkanah brings it to mind here. Remember, Jacob had two wives. By Leah he had six sons; by the handmaids, Bilhah and Zilpah, he had two sons each. At that point, Jacob had ten sons. Only after this did Rachel conceive, and eventually bear two sons. Ten sons and two sons. “Am I not better to you than ten sons?” Even though all the other women bore Jacob ten sons, he loved Rachel more. Elkanah is saying, “I love you as Jacob loved Rachel.”

But it is cold comfort to a woman who wants to be a mother. Hannah is The Barren Woman. Because we know this story framework, we anticipate the likely positive outcome. But the delight is in the details, how the expected outcome takes place—or is frustrated. And Hannah would not be in this book if she did not take the initiative, seize or create opportunity.

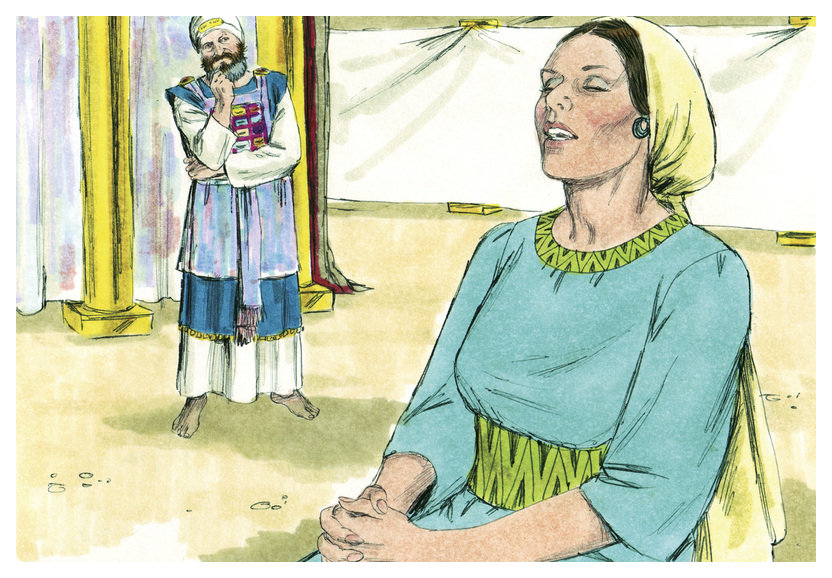

So Hannah rose up after they had finished eating and drinking in Shiloh. Now Eli the priest was sitting on his seat by the doorpost of Yahweh’s temple. She was in bitterness of soul, and prayed to Yahweh, weeping bitterly.

She vowed a vow, and said, “Yahweh of Armies, if you will indeed look at the affliction of your servant, and remember me, and not forget your servant, but will give to your servant a boy, then I will give him to Yahweh all the days of his life, and no razor shall come on his head.”

If you thought that saying this story “begins with one woman’s anguish,” an overstatement, look at this prayer. Describing “The affliction of your servant,” she asks explicitly for a son, which she will then give up! Further, she has pledged that the son will be a Nazarite, a special calling described to Moses in Numbers 6 (for purposes of space I abbreviate):

‘When either man or woman shall make a special vow, the vow of a Nazirite, to separate himself to Yahweh, he shall separate himself from wine and strong drink. . . . vinegar of wine, or vinegar of fermented drink, . . . any juice of grapes, nor eat fresh grapes or dried. . . . he shall eat nothing that is made of the grapevine, from the seeds even to the skins.

. . . no razor shall come on his head, until the days are fulfilled, . . . He shall let the locks of the hair of his head grow long.

. . . he shall not go near a dead body. . . .All the days of his separation he is holy to Yahweh.

The vow of the Nazirite could be for a set time, usually several months. But Hannah has set the time at “all the days of his life!” She asks a lot of God; she also offers to give up a great deal.

We know the burden of Hannah’s heart because the inspired author tells us, but she does not parade her affliction, does not seek sympathy from one and all. Suffering has not made her a bitter complainer. Even in prayer she remains silent.

As she continued praying before Yahweh, Eli saw her mouth. Now Hannah spoke in her heart. Only her lips moved, but her voice was not heard.

Therefore Eli thought she was drunk. Eli said to her, “How long will you be drunk? Get rid of your wine!”

What an unexpected turn in the story framework of The Barren Woman! Usually, when a barren woman encounters a priest, a prophet, or angel—any messenger of God—the messenger assures her that God has heard her petition; that she will conceive and have a son. But here, with Hannah in fervent prayer, she encounters Eli, High Priest and Judge of Israel, who immediately concludes that she must be inebriated. As often happens, this tells us more about Eli’s expectations than it does about Hannah. Once again, we see rich irony. Hannah has pledged that her son will never touch strong drink; and as she makes that vow, Eli suspects her of being drunk.

That’s because drunkenness and debauchery had become so commonplace, even near the tabernacle, that Eli expected to see it. If we did not realize before, this exchange alone warns us of the desperate situation Israel finds itself in.