- Cultural Cousins: Canaanites and Israelites shared common ancestry and cultural ties.

- Religious Struggles: Israel’s recurring idolatry and Canaanite worship led to challenges.

- Balancing Act: Ancient Israel grappled with the tension between engagement and separation in their pursuit of faithfulness.

With all the negative information concerning the Canaanites, it’s easy to forget that they shared both a culture and common ancestry. In effect, the Canaanites and the Israelites were cousins. And that explains a great deal about Israel’s struggles before the Babylonian conquest and Jewish exile.

Israel repeatedly fell into idolatry, worshiping the Canaanite gods. Indeed, the episode of the Golden Calf showed that despite 400 years of Egyptian dominance, Israel retained the knowledge and propensity to worship a Canaanite god.

If that was not enough, once the occupied the Land of Promise, they were surrounded by people with whom they shared a culture and genetics. The Canaanites looked like them, dressed like them—unlike the Egyptions—shared foods, and a general world view.

All these factors explain how Canaanite culture and religion had become the “default” position for Israel—what they fell back into when they ceased their devotion to the God who had chosen Abram, and who had raised up Moses as part of His plan to deliver them from Egypt.

And, like all humans I know, they too frequently reverted to the default Canaanite culture. Moses told Pharoah to let God’s people go “so that they might worship [Him].” When Moses seemed to linger atop Mt. Sinai, they made a Golden Calf, whom Aaron declared to be “your gods, who brought you out of the land of Egypt.”

This incident reveals several things, but it certain clearly demonstrates Israel’s default understanding of deity. Whether they think Moses has been taken hostage or died atop the mountain, they react by making the Golden Calf and presenting offerings to it.

After the conquest, the Bible records repeated incidents of worshiping the gods of the neighboring Canaanite nations throughout the time of the Judges and the time of the Kings. Which God cited as the reason for the exile.

After the exile, following a brief episode of worshiping the gods of the Canaanites as recorded in the book of Nehemiah, Israel had a different problem. Martin Luther said that Christians resembled a drunk who fell off of one side of the horse, and then remounted and fell of the other side of the horse. That’s what Israel largely did after the Exile.

Having been taken captive because they continually intermarried with and worshiped the gods of their neighboring—and related—nations, the Jews strove to avoid repeating that fate by being radically separate. That’s what led to the elaborate regulations regarding ritual purity as exhibited by the Pharisees in Jesus’ time.

That was the problem faced by ancient Israel: should they be close to their “Cousins” or separated from “Others?” How could they be a “light to the nations” (see Isaiah 42:6), without engagement? And how could they engage without being corrupted?

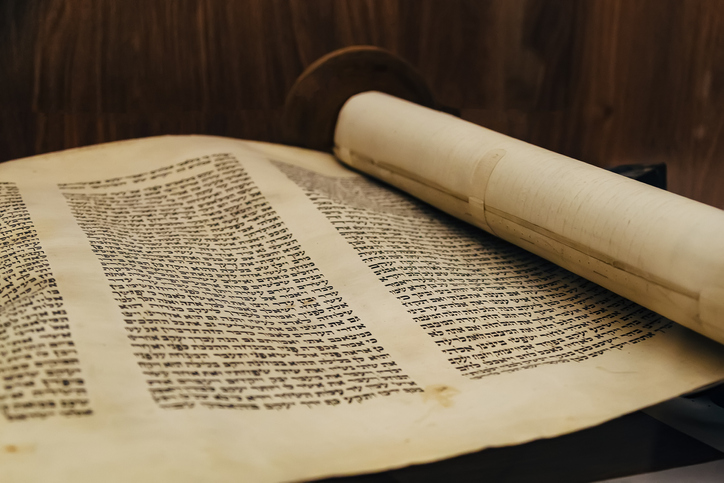

Reading scripture as it was meant to be read, we can learn a great deal about the dangers and remedies confronted by followers of God in all ages—including, perhaps, our own?