What causes some children to adopt their parents’ faith and others to change churches or even leave all faith behind? What makes the difference between staying with a church out of cultural tradition and making the beliefs of that church one’s own? I don’t have the answers, but they are significant questions to ponder as we consider the Leatherman family.

In 1746 Jacob Ledterman, a founding member of the Bedminster, Pennsylvania Mennonite congregation, helped build their first meeting house, one of the earliest in Bucks County, not far from Philadelphia. Ledterman had been born in Germany in 1709 and immigrated to the colony of Pennsylvania in 1741, one of hundreds of German Protestants who migrated at the invitation of William Penn and his sons. Subsequent generations of Leathermans (variations include Ledterman and Letherman, but Leatherman is the most common modern form) remained faithful Mennonites, migrating west in groups to communities in Ohio and Indiana still known for their Mennonite and Amish populations: Medina County, Ohio and Elkhart County, Indiana. But one branch of the family broke away.

After marrying fellow Mennonite Elizabeth Moyer in 1851, Joseph Overholt Leatherman lived in Elkhart County, Indiana until about 1857 when he moved his young family to Plainview in Wabasha County, Minnesota. His three oldest children were born in Elkhart County. In Minnesota, nine more children joined the family, including Martin who arrived on December 29, 1858.

According to the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, there were no Mennonite churches or communities in Minnesota before the first Mennonites arrived in Cottonwood County in 1873. And while the Leatherman migrations from Pennsylvania to Ohio and Indiana appear to have happened in family and congregational groups, Joseph’s move to Wabasha County appears to have been an isolated action. He evidently did not have later contact with the Cottonwood County Mennonites. And it appears that most other members of his family remained Mennonite–His brother Martin was ordained as a Mennonite minister in 1880–so this break with the church of his birth and his family was significant.

We can only speculate as to why Joseph moved his family alone to Minnesota around 1857. Like others moving westward, he may have been seeking better farmland and economic opportunities. But considering the Mennonite communal social structure, that Mennonites had recently established communities in Ohio and Indiana for these very reasons, and that Joseph’s household moved alone, better opportunity does not seem the likely reason for this move. It seems much more likely that he moved because of a falling out with his Mennonite brethren, whether from a personal disagreement or a change in beliefs. When Joseph moved to Minnesota, he was taking his family to the wilderness. In 1850, Wabasha County boasted 274 residents. By 1870 there were three churches–Methodist, Congregational, and Episcopalian. Joseph joined the Methodist church, which was probably the only church when he moved in the late 1850s.

If Joseph did not have prior reasons to break with the Mennonite church, his military service would certainly have caused it. He enlisted in the Minnesota 1st Light Artillery Battery on January 4, 1864. Shortly thereafter he would have joined his regiment in Vicksburg, Mississippi, serving as a private in the western war theater, and ultimately participating in Sherman’s famous march to the sea. Joseph mustered out on June 30, 1865.

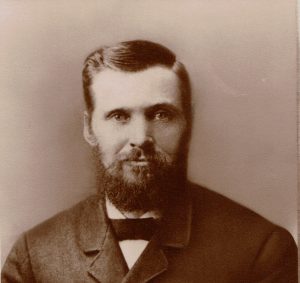

Martin Leatherman around 1900

This then is the fascinating world into which Joseph’s son, Martin Leatherman, was born and raised, and from which he chose to join the Seventh-day Adventist church. But once again the how or why is a mystery. Apparently neither his parents nor any of his siblings made the same decision. According to his obituary, Martin joined the Adventist church around 1900. But in fact he became an Adventist much earlier. He received his first license from the Minnesota Conference on June 19, 1893, which means he would have already gained the confidence of conference leadership in his commitment to the faith. In fact during the summer of 1894 he labored with F. B. Johnson, conducting tent meetings rather unsuccessfully in Lamberton and Revere. Attendance was low and after a short time in Revere, they packed up the tent and returned home. Martin was living in Garden City near Mankato by this time.

So if Martin joined the Adventist church at an earlier date, might one locate news of a particular evangelistic effort or the founding of a new church in this area of Minnesota that would account for his conversion? Or perhaps his in-laws, the Kendalls, were Adventists and he married into the church? As nice as the latter theory sounds, there is no evidence that any of the Kendalls were Adventist before Martin married Cora Kendall on October 25, 1883 in Garden City, Minnesota. Cora’s brother, Albert Wallace Kendall whose wife Olive joined the church in 1887, did not become Adventist until about 1897. In fact, Olive’s decision in 1887 may provide a better clue to the date on which Martin and Cora joined the church.

Finding a significant church growth event that may be connected to Martin’s conversion comes up equally empty-handed. According to the Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia, the church at Mankato–the congregation with which Martin was long associated– was reorganized in 1886, indicating a church was already established at an earlier date. However, in 1883 congregations were established in nearby Eagle Lake and Good Thunder. The Minnesota Conference in fact is one of the earliest organized units of the Seventh-day Adventist church. Evangelism in the region dates back to 1856 with serious effort beginning in 1860, and the Minnesota Conference was formed on July 19, 1863. The Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia notes that “during the succeeding years, the [Adventist] message continued to spread throughout the state through evangelistic meetings and personal work.” It seems most probable that Martin and Cora joined the church through the personal work of an unnoted laborer.

Martin clearly desired to be a minister. He is listed among Minnesota’s licentiates in 1894 and 1895, but then there is a gap in the yearbooks until 1904 when he is no longer listed. So it is difficult to determine what happened in between. In 1894, Martin was also designated Minnesota Tract Society Director for districts 1 and 2. In 1898 he was among the Review’s Greek homeschool course students. And a brief reference in 1901 indicates he may have taught school at Mankato for a short time. The 1890 U.S. Census was mostly destroyed in the first half of the twentieth-century so it is not available to offer us any clues today. (He doesn’t appear to have been counted in the 1880 census, probably because he was unmarried, did not have his own residence, and was not living with his parents who had moved to Holt County, Nebraska. It was during this time that he also made the move from Plainview to Garden City.) The U.S. Census reports for 1900 and 1910 state that Martin’s occupation was farming. But interestingly the 1920 census, taken shortly before his death, claims Martin was a minister. With this scant evidence it appears that Martin’s ministerial career was rather limited.

So what prevented Martin from effectively serving as a minister? The best clue is a personal testimony published on March 28, 1907 in the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, in which Martin shares that he traveled to the Arizona Sanitarium in Phoenix in 1904. He does not reveal how long he had been sick, but stated “pulmonary tuberculosis had reduced me much.” He also hints at a prolonged illness, which had perhaps gone untreated. Many people expected him to die. His weight had dropped below 128 lbs. But most telling is his advice to others:

To anyone who may be suffering as I was, let me say: Do not wait until you are down. Face the probabilities in the case, learn the facts though they be disagreeable and serious; then without delay, combat the disease by taking advantage of every natural element our kind Father has given in sunshine, air, water, and food, at the same time remembering that the proper use of natural remedies is no denial of the faith we profess.

In Martin’s day before antibiotics, or a good understanding of microbiology and the benefits of sunshine, fresh air, and a healthy diet, Martin’s recovery from an almost sure death-sentence would have seemed miraculous. At the time of writing Martin had made at least two visits to the Arizona Sanitarium over nearly two and half years. He returned to Minnesota greatly strengthened, but did continue to struggle with his health, and so made a decision to move to North Dakota in search of a more healthful climate. In 1916 A. W. Alway reported in the Northern Union Reaper, “I have been much pleased to meet our dear Brother Leatherman, a former much esteemed laborer of the Minnesota Conference. Brother Leatherman thinks the bracing climate of North Dakota will be helpful in his fight for health, and we feel that his presence will be a great help to the cause of truth in this part of the field.”

Despite Martin’s long-term struggle for health and the limitations it must have placed on him, he served however he could. When the Missionary Acre Fund was created to pay off debt on the former Battle Creek College property, his pledges were published in the Review (a day’s work in 1902 and $2.00 in 1903). In 1915 the Northern Union Reaper reported Martin’s nomination as elder and auditor for the Mankato church. He most likely served as church elder earlier than this date as he officiated at a church member’s funeral in late 1907. After his move to North Dakota, Martin continued some sort of evangelism in the communities of Heart and Beach.

Martin and Cora were counted in Beach, North Dakota in the 1920 census, but whether they moved immediately after this or were simply visiting their children who had relocated to Battle Creek, Martin died in Battle Creek, Michigan August 8, 1920. He was buried in Garden City, Minnesota. In his obituary he was noted for a “consistent Christian life.” Another obituary says, “He was a loving father, a hard church worker, and true to his God.”

Unlike Joseph and Martin, who left their parents’ churches, at least five of Martin’s children chose to become Seventh-day Adventists. Through his daughter Elsie’s line, there are currently four generations of Martin’s grandchildren who are active members in their local congregations. They have chosen to make the Adventist message their own faith.

Sabrina Riley recently resigned as library director and historian at Union College. She is currently a military wife, homeschooling mom, and independent researcher in Northern Virginia. Her current research interests include the Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps, Union College-related entries in the new Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists, and her family’s genealogy.