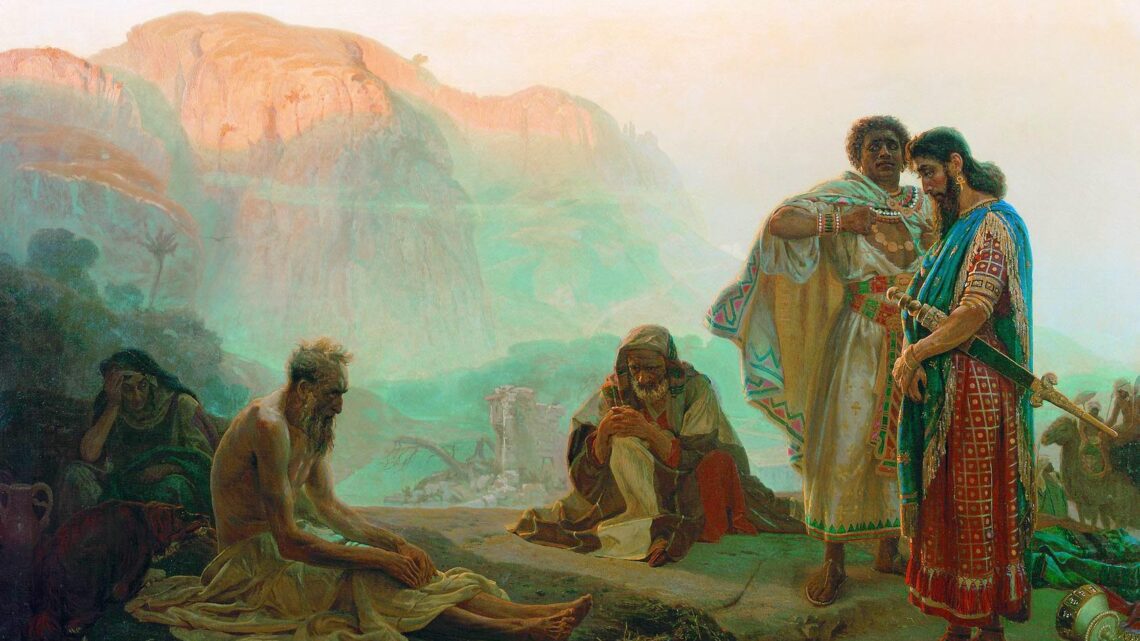

As we read the text of Job, we immediately ecounter a riddle. Job, declared to be “blameless, upright, fearing God, and turning away from evil,” suffers a series of terrible losses, beginning with his wealth in the form of livestock and servants, and extending even to loss of all his children. On top of that, is stricken with dire physical pain and affliction. All this baffles Job—indeed, it baffles us.

We are taught, and scripture affirms, that if we do right, we will be blessed. The psalmist says this explicitly:

Blessed is the one

who does not walk in step with the wicked

or stand in the way that sinners take

or sit in the company of mockers,

but whose delight is in the law of the Lord,

and who meditates on his law day and night.

That person is like a tree planted by streams of water,

which yields its fruit in season

and whose leaf does not wither—

whatever they do prospers.

Psalm 1:1-3 NIV

“Whatever they do prospers.” That certainly describes Job’s status as the book begins. First it describes his character, as quoted above, then it lists his riches, finishing with the declaration “He was the greatest man among all the people of the East.” It almost seems like a mathematical equation: Job does right = everything he does prospers. In Job’s world—and our own—everything makes sense.

Then the series of disasters strikes, and nothing makes sense. To anyone in Job’s world. So everyone does what any of us would do: they try and make sense of it all.

Job’s wife concludes that God has unjustly punished him, and tells him he should “Curse God and die.”His friends wrestle with the same problem, but cannot bring themselves to condemn God. They then come to comforting—at least comforting to them—conclusions: since God cannot be at fault, then Job or someone close to him must have done something terrible; terrible enough to justify God visiting such horrific judgments on him.

Eliphaz, the first to speak to, him tells Job it’s his fault. Bildad, speaking second, piles on telling him that his children had caused their own destruction. If this round enough, Zophar piles on by telling Job, in essence, “You’re getting off easy. You deserve worse.”

Job is having none of it. He knows he has not done anything to deserve all this. He appeals to God beyond the God is friends are talking about. He has been treated unfairly, and he knows it. And so do we, the readers. We all intuitively believe that someone who does good things should receive good things, and someone who does bad things should be punished. But so far, the events in Job have turned our intuitive believe on its head.

We are told that Job was blameless and upright and so on, yet he has been struck with terrible trials. This forces us to confront with one of the great philosophical questions of all time: “Why do bad things happen to good people?”

The rest of the book of Job presents us with another unanswered question. God never tells Job why all these terrible things happened to him. Why/ When God confronts Job, He asks Job a series of questions to which there is no answer. He asks questions which demonstrate His great power: he can set a limit on the sea, he can move the stars in the heavens, he feeds all the animals of the field; can Job, He asks, do any of these things?

At the end, Job accepts that he will not receive an answer, and that if he did receive an answer, it would be beyond his comprehension. Job’s only choice is to trust the God who does all these miraculous things, or to judge Him unworthy of trust.

But the book of Job does not similarly challenge the reader, for it includes two scenes of which Job and his associates know nothing. Those scenes give us insight to the events in Job, but leave two other questions unanswereed.

We examine those soon

- The Riddle of Job’s Suffering: Job is described as a righteous and blameless man, yet he suffers immense loss and affliction, which challenges the conventional belief that good people should be blessed and bad people should be punished. This leads to the central philosophical question: Why do bad things happen to good people?

- The Friends’ Responses and Misunderstanding: Job’s friends, unable to reconcile his suffering with their understanding of divine justice, suggest that he must have done something wrong to deserve such punishment. Job, however, insists on his innocence and rejects their accusations, emphasizing the apparent injustice of his situation.

- God’s Silence and Job’s Trust: God never provides Job with an explanation for his suffering. Instead, He challenges Job with questions that highlight His own power and sovereignty. In the end, Job accepts that he will not understand the reasons behind his suffering and must choose whether to trust God or not, even without an answer. The book leaves readers with unanswered questions but invites them to reflect on God’s mysterious ways and the limits of human understanding.