In my previous post, Making the Case for Local Church Histories, I discussed some of the reasons preserving local church history is important. Now it is time to talk about how to uncover that history.

Local church history is family history. Uncovering the story of your congregation requires many of the same research techniques and resources as discovering the story of your family and the communities in which they resided. Quite likely, the history of a local church will be intertwined with that of the families who make up the membership. This is certainly true of my family.

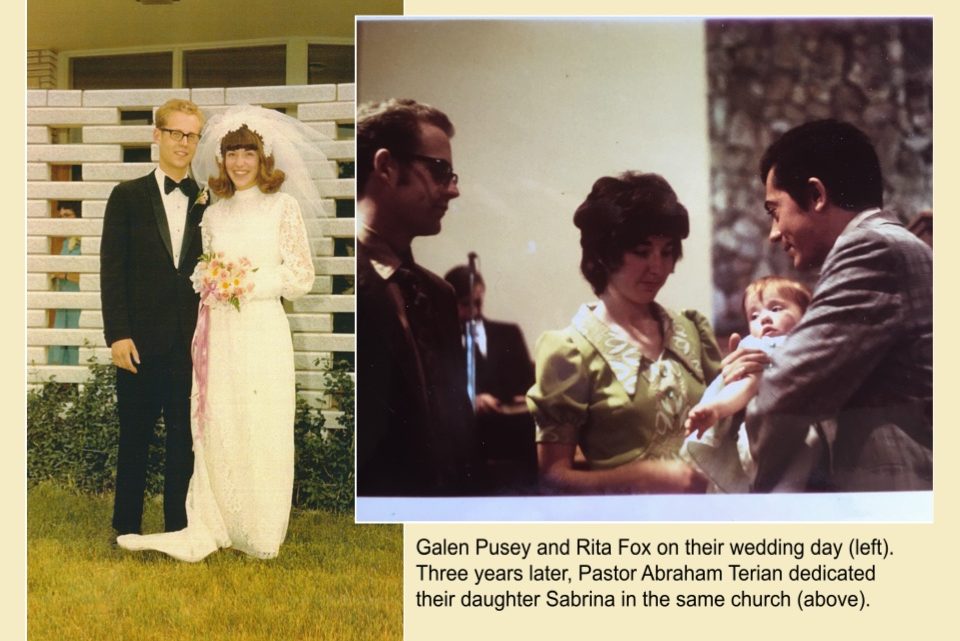

When my parents married in 1971, theirs was only the second wedding to be held in the present Dowagiac Seventh-day Adventist church. I was dedicated in the same building three years later. In sixth grade, I was baptized in this church, and at the end of my elementary school years, my eighth-grade graduation ceremony was held in this building. Years later, the ladies of the church hosted a wedding shower for me in the basement fellowship room. Our family photo albums include pictures from church school programs, church campouts, and numerous church social events.

The duration of your relationship with your local church may be long or short; regardless, your personal knowledge is the starting point of your research. That personal knowledge may be your own history with the congregation, or it may be your acquaintance with other members of longer standing.

Begin your research by writing down everything you know and remember.

When I was dedicated in the Dowagiac church, the building was only six years old, and the congregation had been organized about twenty-nine years earlier. I attended (as a child) and was a member of this church for another twenty-eight years. In addition, I have retained a close relationship with it through family and friends who remain there, as well as through frequent visits. This means that I have memories of several of the founding members and was friends with even more long-term members. Between listening to their stories and my own experience, my personal knowledge encompasses seventy-six years of the congregation’s history.

Interview the church members who have been part of the congregation the longest.

Whether your connection to the church is long or short, it is still important to gather information from as many members as possible. As you speak with people, ask to record their stories, and collect copies of their church-related photographs and memorabilia. Gathering many perspectives provides a fuller picture of the congregation’s history. It is now too late for me to interview those early members, but I am still talking with others who have been part of the Dowagiac church for a long time, even if that is a similar timeframe to my own. Together, our collective memory remembers more than one person’s alone.

Search online denominational archives for references to your church.

You just might be surprised at what you find. The Dowagiac church’s collective memory vaguely recalled a branch Sabbath School meeting in a house in the 1950s and wasn’t sure when the church was organized. Searching the Adventist Digital Library revealed a much older and more complex history. In fact, an Adventist church in Dowagiac has been organized on three separate occasions: 1873-1874, 1920, and again in 1945.

The Adventist Digital Library is a single platform of fulltext content for published resources from across many denominational organizations. The Seventh-day Adventist Periodical Index is a searchable index for Adventist magazines. It is more useful for finding information published in the last forty years. You can also use the Seventh-day Adventist Obituary Index to locate obituaries of deceased pastors and church members. The General Conference Archives also makes archival collections available online.

Search local history resources such as newspapers and city directories for references to your church. These may be found at your local public library, historical society, and sometimes online.

As previously mentioned, collective memory recalled the Dowagiac church meeting in a house before the present building was constructed. Searching city directories revealed the addresses of several more locations. It is also hoped that networking with people interested in Dowagiac’s local history will unearth photographs of these locations.

Visit an Adventist archival repository such as the Center for Adventist Research or the Union College Heritage Room.

These repositories may possess print resources with even more information. At the Center for Adventist Research using student newspapers, I have discovered that students from Emmanuel Missionary College were conducting evangelism in Dowagiac in the 1920s, and reviewing Michigan Conference directories uncovered more addresses for places the congregation met over the years. Conference directories will also list pastors and key church officers such as head elders, treasurers, clerks, and Sabbath School secretaries. They may include statistics about church membership and help confirm dates the church had an active congregation. Barring your ability to visit one of these repositories, you may find a stash of old conference directories in a closet somewhere in your church building.

Work with your church clerk and treasurer to gather local primary sources.

Primary sources include board meeting minutes, membership records, bulletins, church directories, lists of church officers, and financial records. Both the treasurer and church clerk are ethically bound by confidentiality, so they will not be able to open sensitive records to you. They can provide copies of any reports prepared for the church as a whole. Rather than asking them to open records to you, compile a list of specific questions for them to answer using the records in their possession.

So far, my discussion may make research look like a linear process. It is not. I mention the primary documents held by the clerk and treasurer last simply because you will better know what questions you need to ask once the prior research is well under way. However, throughout the entire process, as new discoveries are made, you may need to circle back to a prior step. For example, you may find information in secular sources that sends you back to church publications for additional information and vice versa. As you make new discoveries in published material, you may want to share it with older members to help interpret it correctly. Likewise, primary sources—including contemporary publications—should usually be considered more reliable than human memory, but not always. Research often requires one to reconcile conflicting information and make judgment calls about which sources are most reliable.

Finally, take careful notes at every step of the research process.

Your final product will be both a social and an institutional history. Institutional history includes important dates, founding documents, pastors names, church officers, membership statistics, financial information, evangelists who have conducted meetings in your town, and the addresses or locations where the church has met over the years. While this information is not always interesting by itself, it is descriptive and provides an important framework for the congregation’s social history.

Social history is the narration through which your readers connect with their history emotionally. As you interview older members and read through the archives, note interesting stories and significant people—both those who have been instrumental in maintaining the local church and those who have left for work of distinction in other places. Often certain families will have played important roles. Merrill Y. Fleming was a Michigan Conference youth leader for many years. He grew up in Dowagiac, and his family sold the land to the Dowagiac church on which the building now stands. He and his brothers used to play ball on the lot. When he returned to Dowagiac each spring for Pathfinder Investiture, it was a little homecoming event. But equally important are the steadfast pillars of the local congregation who often go unrecognized. For all of my childhood, Charles and Betty Koudele were at the center of the Dowagiac church’s life. They were among the early members who built the present building and served as elder and clerk, respectively, for decades. No history of this church is complete without mentioning their contributions. In addition, no church history is complete without situating it within the histories of both the local community and the Adventist denomination. Dowagiac’s proximity to the Seventh-day Adventist Seminary at Andrews Univeristy means that many seminary students have attended the church before moving on to greater careers, including lifelong Adventist Frontier missionaries and General Conference employees. Understanding the history of the local community can offer explanations as to why the church has struggled to grow or how it has played an integral role in the community.

Once you have collected your source material and compiled your notes, it is time to write. My next article will address how to write a local church history.