I would like to say a few words to my dear brethren, through the Review. I feel to praise the Lord for his abundant goodness to me, while passing through the trial which I am called to endure . . . In accordance with the instructions given through the Review by Bro, J. N. Andrews, I reported myself as a non-combatant, and upon the presentation of the evidences of my position, received a certificate from the Provost Marshal, giving a statement of the facts: 1. Showing that I had procured evidence and satisfied the board of enrollment that I was a non-combatant, within the meaning of section 17 of the act approved Feb. 24, 1864. 2. That I was entitled to the benefits and privileges of said section. (Advent Review and Sabbath Herald v.25 no.9. Pg. 70)

Thus Philander Houghton Cady reported his first action upon being drafted into the Union Army on November 2, 1864. Cady was assigned to the 37th Wisconsin Infantry that had been organized at Camp Randall in Madison, Wisconsin in the spring of 1864. By the time Cady joined the regiment it had already been in position along the Petersburg, Virginia siege lines since May of that year.

Cady was able to claim non-combatant status gratis of the Quakers’ lobbying efforts and the recent legal organization of the Seventh-day Adventist church. Civil War conscription was not liberal toward conscientious objectors. Adventists and other conscientious objectors had three options: enlist when drafted, pay a $300 commutation fee to avoid service–an exorbitant sum for the modest income of a Wisconsin farmer and carpenter–or provide proof of membership in a federally recognized religious body with a tradition of conscientious objection. The latter was tough to prove as the Adventist church was still in its infancy. The first conscription law was passed almost three months before the formation of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists.

Becoming Seventh-day Adventist

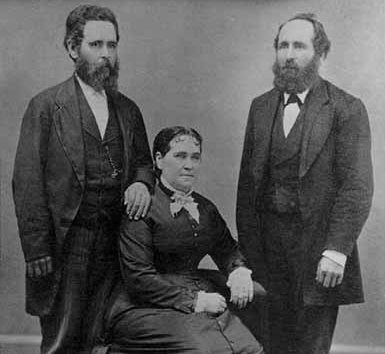

Born in Vermont on August 20, 1832 to Jacob Cady and Betsey Emeline Coolidge, Philander Cady moved to Indian Territory just north of Marquette County, Wisconsin with his parents and siblings in about 1850. Soon after their arrival the area was organized into Waushara County. Jacob Cady was one of the first four residents of the new town of Poy Sippi. Philander Cady married Nancy Jane Hall on March 17, 1850 in Poy Sippi, Wisconsin. The couple eventually had eleven children.

In the summer of 1857 Cady took a job constructing a barn for a farmer near Mackford, Wisconsin. At the same time, J. N. Loughborough, in partnership with Elders Josiah Hart and Elon Everts, was conducting tent meetings in town. Cady may have already had Adventist leanings, but it was not until these meetings that he became convicted of the seventh-day Sabbath. One Sunday, he spent the entire day listening to a presentation on the Sabbath and the law. Taking careful notes Cady fully believed that a thorough Bible study would refute the seventh-day Sabbath. Instead he was converted. And over the next half century, the ripple effect of Cady’s decision would travel halfway around the globe.

Returning home to Poy Sippi, Cady shared his new discovery with his mother and soon a small group was meeting in the home of Jacob and Betsy Cady. Cady’s own carpentry skills were later called upon to build the first Seventh-day Adventist church building in Poy Sippi. Besides his carpentry work, Cady was also a talented violinist and conducted singing schools. Through this work he became acquainted with a Baptist minister, John G. Matteson, who also conducted singing schools and played the violin. According to Cady’s son Marion E. Cady, the two friends would hold long theological debates, pausing to play and sing when the debates became too heated. Matteson finally accepted the seventh-day Sabbath, and after a successful evangelism ministry among Danish and Norwegian immigrants in the Midwest that included converting his entire Baptist congregation, Matteson and his wife were appointed the first official Seventh-day Adventist missionaries to Scandinavia in 1877.

It is difficult to determine which of Cady’s family members became Seventh-day Adventist, but examining obituaries listed in the Seventh-day Adventist Obituary Index provides some valuable clues. As already mentioned, Cady’s mother was an early convert, but it appears that his father never joined the church. Cady’s wife and all of his children joined the Adventist church. Less certain is which, if any, of his siblings became Adventist.

Among Cady’s siblings, his brother Benjamin Adelbert Cady, appears to have had at least a peripheral interest in the church. Benjamin’s name appears in the Review on at least two occasions: In his first wife Julia Ann Shepard’s obituary (she joined the church 1867) and after his mother’s death when he gave money to the Review in her memory (1906). His daughters Lucinda and Myrtle were also Seventh-day Adventists. But when Benjamin died in 1920, the local newspaper obituary stated he was a member of the Congregational church, and described him as a student of the Bible.

In the Army of the Potomac

Whether or not the brothers shared any religious experience, they did share their army experience. Benjamin was drafted November 25, 1863. He was assigned to Company I of the 37th Wisconsin Infantry. Company I joined the regiment at Arlington Heights on May 17, 1864. After a brief duty in Washington, D.C. the regiment headed south to participate in General Grant’s final, although protracted, campaign to take Richmond. Consequently, Benjamin was involved in the fighting at Petersburg throughout June and July 1864. The 37th suffered heavy losses during these months including at the ill-fated Battle of the Crater at Petersburg, Virginia on July 30, 1864. The 37th was also active in the final days of the war leading up to the fall of Petersburg and Richmond and the surrender at Appomattox. Apparently Benjamin was wounded in one of these final actions, losing the middle and index fingers on his right hand (1890 Veterans Schedule).

After the substantial loss of men during the summer of 1864, the 37th was in need of more men. As mandated by law, Philander Cady had registered for the draft in July of 1863. Now he was drafted on November 2, 1864. He formally enlisted on the 15th of the same month because he could not afford to pay the $300 commutation fee that would have excused him from service. Despite satisfying the requirements of the law documenting his noncombatant position, upon reaching Madison, Wisconsin he too was assigned to the 37th Wisconsin Infantry, albeit, a different company from that of his brother.

Cady did not say why his noncombatant certificate was not honored in Madison. Perhaps the officers in charge were too harried by the demand for more soldiers to trouble themselves with such an accommodation. Or perhaps they did not have the authority to assign Cady to hospital duty as he desired. Cady was told he must be assigned to a regiment and sent south. Once in Virginia he could talk to his commanding officer about a transfer.

But once he reached the regiment’s camp, a transfer was not so easily obtained. The regiment’s commander was not familiar with the legal provisions for noncombatants and Cady had to explain the law to him. The commander offered to make Cady camp cook, but Cady protested against even that position. So his certificate was sent up the chain of command and ten days later he was notified that his request for noncombatant duty was denied because he failed to meet the requirements of the law. This is where Cady ends his story. Government records show that he remained with the 37th in Company K until the end of the war, so he never was transferred to a hospital. However, what duties he was assigned in Company K have been lost in the mist of time.

Cady’s quest for non-combatant status may have been unsuccessful, but by joining the army so late in the war, he was able to avoid most of the fighting. In fact, the 37th’s regimental history after November 1864 is rather unexciting. It was spent mostly in winter encampment and miserable wet muddy marches. Cady himself

described slogging through Virginia’s rainy winter season. To add to his discomfort, Cady also suffered “chronic diarrhea” throughout the winter (1890 Veterans Schedule). In the Review he shared his abhorrence of the other soldiers’ profanity. But in spite of the rough conditions, he tried to keep a cheerful spirit, sought opportunities to witness to other soldiers, and maintained his faith in God.

The Ripple

Cady’s brother Benjamin was mustered out June 20, 1865 when all of the sick and wounded from the 37th in hospitals around Washington, D.C. were discharged. Returning to Poy Sippi, he studied to became a lawyer, then moved to Birnamwood, Wisconsin in 1867, and became active in local politics. Benjamin died November 27, 1920.

Philander Cady was mustered out with the rest of the regiment on July 27, 1865 and formally discharged from the Army on August 15, 1865. He returned home to Poy Sippi, Wisconsin where he continued to farm and work as a carpenter until about 1883 or 1884 when he was ordained as an Adventist minister. As a minister, Cady was a delegate at the 1888 General Conference Session.

More importantly, Cady and his wife raised a large family for service in the Adventist church, an influence felt far and wide. Among their eleven children, Matthew Philander Cady became a teacher and later a physician. Benjamin Jacob Cady became a missionary and sailed to the South Pacific on the second voyage of the Pitcairn. Ulysses Thomas Cady– reportedly baptized by James White–attended Battle Creek College, became an educator and later taught at Washington Missionary College (now Washington Adventist University). Marion Ernest Cady also became an Adventist educator and served as president of Washington Missionary College for a time. Daughter Vesta Jane married A. D. Olsen with whom she undertook evangelistic work in the north central United States. Three years after Olsen’s death in 1890, she became Eugene W. Farnsworth’s third wife. Together they served the church in Australia, New Zealand, England, New England, and California. Mary Emeline married Alfred W. Jorgensen and their son Guy Cady Jorgensen became a longtime Chemistry professor at Union College (the science classroom building demolished in 2014 was named in his honor).

At the end of his life Cady was diagnosed with “internal cancer.” He died on February 7, 1897 (his tombstone is incorrectly engraved 1896) in Battle Creek, Michigan while seeking treatment at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. Cady is buried in Poy Sippi, Wisconsin.

Sabrina Riley is an independent researcher and consultant in Northern Virginia. Her current research interests include the Seventh-day Adventist military experience and her family’s genealogy. She may be reached at The Family Archivist .