His name appeared repeatedly in the pages of the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald and other Adventist magazines between 1882 and 1904. As recorded in their obituaries, he is credited for the conversion of countless Seventh-day Adventist church members. He helped establish congregations in the towns of Grinnell, Granville, and Waukon in Iowa; Norwich, Connecticut; Westerly, Rhode Island; and probably many more. He was much in demand as an evangelist, lecturer, and camp meeting speaker. In 1895 he traveled from his home in New England to speak at camp meetings in Colorado, South Dakota, and Kansas. The following year his itinerary extended north to Quebec, Canada and south to Florida, with stops in Georgia, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. This was in addition to his usual circuit covering much of New England. So why is George E. Fifield relatively unknown today? How did he come to be an Adventist minister? Why was his obituary omitted from church publications? In short, who was George Edward Fifield?

An Orphan

He was born on March 18, 1859 in Nashua, New Hampshire to Rodney and Harriet Frances Nichols. Tragically, Harriet died of typhoid fever before the end of 1859. The U.S. Census for 1860 reports Rodney, infant George, and his older sister, Francelia (Celia), living alone. But the children were soon to lose their father as well.

Rodney Fifield enlisted in Company C of the Massachusetts 2nd Cavalry Regiment on March 31, 1864. Among other assignments, one of his first duties upon reaching Virginia may have been patrolling the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. In June the Massachusetts 2nd Cavalry escorted wounded from the Wilderness battlefield. But most of the action in which Rodney participated would have occurred in the Shenandoah Valley as part of Sheridan’s Valley campaign of 1864. Rodney did not survive the war. He died of tuberculosis (consumption) in a regimental hospital in Winchester, Virginia on February 25, 1865–one of the 141 men from his regiment who died of disease during the war. Ninety others were killed or mortally wounded in battle.

When Celia and George went to live with their maternal grandparents, Freeman and Sarah Nichols of Merrimack, New Hampshire, is uncertain, but it seems likely to have happened well before 1870 when the U.S. Census reports their living arrangements in Merrimack. A former Methodist, Nichols broke with that church over the issue of slavery. In 1840 he become a follower of William Miller. But after the Great Disappointment of 1844, it did not necessarily follow that he would join the ranks of the growing Seventh-day Adventist movement. His obituary claims he joined the Seventh-day Adventist church around 1866. So while their parents’ religious affiliation is unknown, Celia and George Fifield were raised in an Adventist home. Freeman died of cancer in 1884 having lived his entire life on his father’s farm in Merrimack, New Hampshire.

Meanwhile, both grandchildren embraced the Adventist message. On August 20, 1874, Celia married James F. Belden of Rocky Hill, Connecticut. Belden was likely a grandson of Albert and Hannah Belden who graciously shared their home with James and Ellen White in the late 1840s and supported the Whites’ ministry in other ways. It would not be farfetched to suggest that James Belden was James White’s namesake. Celia remained a lifelong Seventh-day Adventist, ultimately living in South Lancaster, Massachusetts where she provided a home for approximately 150 students over thirty years.

A Minister

According to The Ellen G. White Encyclopedia, George Fifield attended Battle Creek College from 1877 to 1879. Following his years at Battle Creek, he likely worked as a colporteur in Iowa before becoming part of Elder L. T. Nicola’s evangelistic team. On June 5, 1882 he was granted a ministerial license (although according to The Native Ministry of New Hampshire by Nathan Franklin Carter, Fifield received his first license in 1881). Later that year he also participated in the Iowa Sabbath School Convention speaking on “Do Sabbath-school Scholars Ever Graduate?” The subsequent discussion concluded that they do not.

The scene of Fifield’s labor moved to New England in 1889 where, among other duties, he became secretary of the New England Religious Liberty Association. Over the next five years, based out of South Lancaster, Massachusetts, he continued preaching across New England, gaining a reputation as an authority on religious liberty, and publishing a number of articles in various Adventist magazines. Fifield was ordained January 18, 1889 in South Lancaster. Then in December 1890 in perhaps the highlight of his career, he served as Ellen White’s escort on her tour of New England. Ellen White praised his work:

I never saw Elder Fifield appear as well as now. Certainly he has success in arousing an interest. He feels the burden of souls on this occasion. He reins them up to a decision and then he says, I weep with sorrow of soul as I see the difficulties that obstruct their way. If anyone feels the love of souls and is brought in interested connection with these souls who long to obey and do not have faith to venture, it will cause soul agony. {16MR 78.1}

Although, Fifield’s name does not appear in the Adventist Yearbook after 1894, it was during the latter half of the 1890s that his speaking engagements ranged widely across the United States. He also served as a General Conference Bible Institute instructor in Atlanta, Georgia in early 1896. So what caused his name to be lost in obscurity?

A Flawed Man

Apparently Fifield was something of a ladies’ man. In a letter written to Willie and Mary White on August 20, 1884, Ellen White frankly recounted calling out Fifield for the inconsistency between his preaching and his behavior outside of the pulpit. The particular issue discussed was the example he set for younger men in his relationships with women. At the time Ellen White thought him unrepentant, so her praise of his work in New England six years later leads one to hope he changed his ways. And perhaps for a time, he did.

On January 14 in either 1886 or 1888 (secondary sources don’t agree, and a primary source has yet to be located) Fifield married Mary Angelica Flood in Smyrna, Michigan. Mary was the daughter of Civil War Brevet-General Martin Flood of Wisconsin and his wife, Prudence Darling. Prudence and some of her children moved to Smyrna following the general’s death in 1877. No connection between the Floods and Adventism is known, so how Fifield met and married Mary in Michigan is a complete mystery.

The Fifields had five children (The Ellen G. White Encyclopedia incorrectly reports four children; the authors were likely unaware of the six-month old baby who died in 1893): Harold Forrest (August 30, 1889-January 1965), Gladys Leona (January 2, 1892-June 21, 1965), Gerald Elsworth (April 8, 1893-October 14, 1893), Mildred Florence (July 19, 1896-December 8, 1918), and Reginald Sumner (December 18, 1899-April 15, 1977). Although little is said about Mary’s activities, Ellen White did mention that Mary accompanied her husband on at least one visit to a church member’s home in December 1890.

The first inkling that all might not be well in Fifield’s ministry and marriage is found in the minutes of the General Conference Committee in 1896 when there was some discussion of where he should be assigned. Taken alone, the discussion might appear to be one of deploying a human resource in the most advantageous location. But given subsequent events, one may read between the lines that questions regarding his suitability for ministry were developing. Rather than represent New England, Fifield attended the 1897 General Conference session in Lincoln, Nebraska as a delegate-at-large, where he testified:

All the honor, all the righteousness, I want in this world, is to know Christ, and have the privilege of preaching his unsearchable riches to others. There is comfort in the thought that the Father is at the helm. He will guide us through. I desire a heart so deep, so tender, so sympathetic, so moved by the impulses of his Spirit, that it will respond in sympathy to the cry of every troubled soul (The Daily Bulletin, Feb. 22, 1897, Pg. 111).

Whatever his weaknesses, Fifield truly had a heart for ministry.

Throughout 1898 Fifield continued to work in New England. In 1899 the General Conference denied a request from Washington, D.C. for Fifield to work in that city. Although his ministerial credentials were renewed, his assignment was unspecified. References to him in church papers up to 1904 indicate that Fifield continued evangelism in New England. These references are interesting, because in 1902, the General Conference Committee recommended that he be moved to a western location and that his speaking engagements be no longer publicized “until he has had time to demonstrate that he is a changed man.” The Ellen G. White Encyclopedia reports he was assigned to California. However the General Conference Committee recommended that he move to Northern Illinois in 1903.

So where did Fifield end up and why did his name disappear in church publications? The 1902 minutes cite Fifield’s criticism of fellow Adventists and inappropriate relationships with women as reasons for his relocation and the subsequent lack of media coverage. Unfortunately the new spiritual maturity Ellen White witnessed in him in 1890 had not lasted. And apparently Fifield never demonstrated the necessary reformation, making it easy to answer why his name disappeared from publication. But sources are confusing as to what he did next.

The Rest of the Story

Sometime between 1904 and 1910, Fifield left ministry in the Seventh-day Adventist church. In 1910 the Federal Census reports he was a manager of a medicine company in Connecticut. Then, sometime between 1910 and 1920 Fifield and Mary divorced. Did the Fifields move to California first? Perhaps. According to the 1920 Federal Census, Mary lived in Orange County, California with Gladys and Reginald. But there is no record that Fifield himself lived or worked in California. Only the undocumented reference in The Ellen G. White Encyclopedia suggests it.

Meanwhile, there is the 1903 recommendation that Fifield relocate to Northern Illinois. The only evidence that he might have made this move does not appear until 1922. Newspaper articles report that he was already a Seventh Day Baptist minister in Chicago, Illinois when he accepted the call to become the pastor of a Seventh Day Baptist church in Battle Creek, Michigan in 1922. In Battle Creek he became a well-respected minister. He remarried on June 6, 1921. His new wife, Alice White, was a native of West Virginia who came to Battle Creek as a sanitarium patient and then stayed on working as a secretary in the same institution. Whatever her previous religious affiliation, she joined the Seventh Day Baptists too.

Interestingly, although we have no information with which to compare how Fifield’s personal beliefs may have shaped his departure from the Adventist church, one cannot help but wonder about his relationship with Alonzo T. Jones. Both men worked closely on the religious freedom issues of the 1890s when there was a major push for Sunday laws across the nation. They appear to have remained friends after they both left the Adventist church. Fifield officiated at Jones’ funeral in 1923. Did Fifield share any of Jones’ criticism of Adventist doctrine and church structure? Is that what was meant by the “criticism of the brethren” referenced in the General Conference Committee minutes in 1902? We may never know the answers to these questions.

Available sources paint a picture of estrangement from his children. Mildred apparently went to live with her Aunt Celia. According to her obituary, Mildred is likely the only child to have remained Adventist, but she suffered from tuberculosis and died young. The absence of any obituary in Adventist publications for Mary or the other three children suggests they all left the Adventist church. Mary, Gladys, and Reginald died in California. Harold remained in Massachusetts where he had already established a railroad career before 1920. When Fifield himself died on July 26, 1926 of a stroke, no mention is made of any of his children, nor of his former association with the Seventh-day Adventist church.

Fifield may have remained a committed Christian and loyal to the seventh-day Sabbath until the end of his life, but it was not enough to save his family. One man’s choice may produce generations of faithful church members or it may prove a stumbling block for them.

Sabrina Riley is a researcher and writer currently living in Virginia.

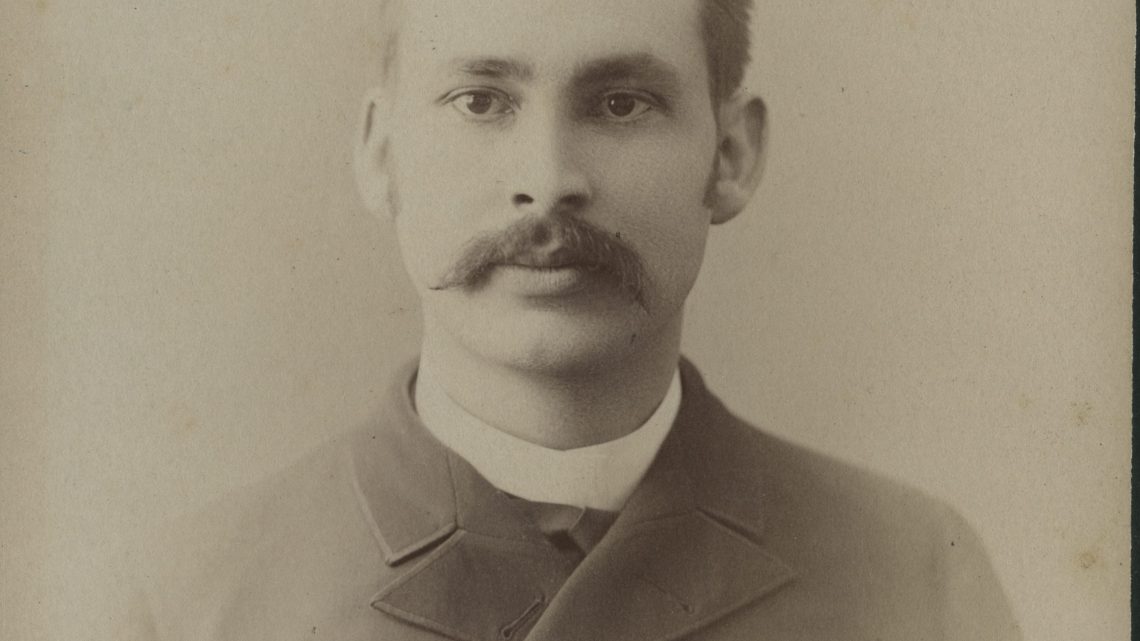

Mary A. Fifield

Photos: Adventist Digital Library