Emaline Schwagerman sticks her tongue out and winks. The camera shutter snaps. She grins and contorts her body into her many different poses while her parents stand politely smiling into the camera. Her excitement and energy show her obvious enjoyment of life as a 10-year-old. “She’ll wear you out,” Bill Schwagerman, Emaline’s father, says with a laugh.

Emaline’s home in rural Missouri is about an hour from Kansas City, and it is a peaceful family property off a long gravel road. But Emaline’s life did not begin peacefully. Her life is the story of a persistent struggle, and the need for that struggle to be told.

Trisomy 21 and a thread of blood

Before Emaline was born, the ultrasound technician was unable to show a clear picture of her heart. All four chambers of the heart had formed, but the ultrasound didn’t display a precise picture of all of them. Everything else looked okay, though, so it was decided it was probably due to how she was positioned in the uterus. “What they didn’t know,” says Emaline’s mother, Dr. Cindy Bracken-Schwagerman, “was that what they were seeing was one of the defects in her heart.”

Emaline was born with tetralogy of Fallot. Of children born with this condition, Cindy says about 10 percent have a right-branching aorta. “Instead of her aorta coming up out of the heart and curving to the left, it curves to the right,” she explains. This is the heart defect that kept the ultrasound technician from getting a good look at Emaline’s heart.

Tetralogy of Fallot is an extremely rare heart defect believed to affect approximately 1,660 babies per year in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). It has unknown causes, but it consists of four problems with the development of the heart that alter normal blood flow through the heart. A hole exists between the lower chambers of the heart, there is an obstruction from the heart to the lungs, the aorta lies over the hole in the lower chambers and the muscle surrounding the lower right chamber becomes overly thickened. In Emaline’s case, the blood flow from her right ventricle into the pulmonary arteries affected how much blood and oxygen made it to her lungs and the rest of her body.

Emaline’s parents found out about her heart defect shortly after she was born. “For me in particular, because of my background in life sciences and animal sciences, it wasn’t something that phased me. I know it is something that can be fixed,” says Cindy. But Emaline didn’t only have a heart defect, she was also born with Down syndrome. “When they took us to the NICU, they said ‘By the way, we sent off a sample of her blood. We think she has Down syndrome.’ We were surprised, because there were no obvious signs of Down syndrome when she was born.”

From that point on, the next year was pretty much a blur. We were in survival mode.

Emaline looked healthy and normal, but the doctors confirmed she did, in fact, have Down syndrome. “She was born a little after 10 in the morning, and it was about 10 at night when we got the diagnosis of Down syndrome. It was a total shock,” says Cindy. “From that point on, the next year was pretty much a blur. We were in survival mode.”

Down syndrome occurs when a full or partial extra copy of chromosome 21 exists in the nucleus of a person’s cells. Usually there are two copies of chromosome 21, but people with Down syndrome have a third copy, often called trisomy 21. Several other health problems often accompany Down syndrome, including heart defects.

Emaline spent the first three weeks of her life in the Level III NICU at Overland Park Regional Medical Center in Overland Park, Kansas. Bill explains that spending those weeks in the NICU reminded them they were not alone in their situation. “There were parents who had been there maybe a month or two before we started our three weeks who were just living there. We saw a side of life we had never seen before. Babies just struggling and fighting for life.”

“We saw things that were so much more difficult than what we were facing,” says Cindy. “She at least had a fighting chance.” And Emaline did fight to stay alive. After about two months, Emaline’s heart defect required surgery. “The muscles around the pulmonary valve enlarged to the point where there was literally just a thread of blood getting into the lungs. That’s when emergency surgery was done.” This was her first open heart surgery. Five heart surgeries, two of them open heart surgeries, were performed to keep Emaline alive.

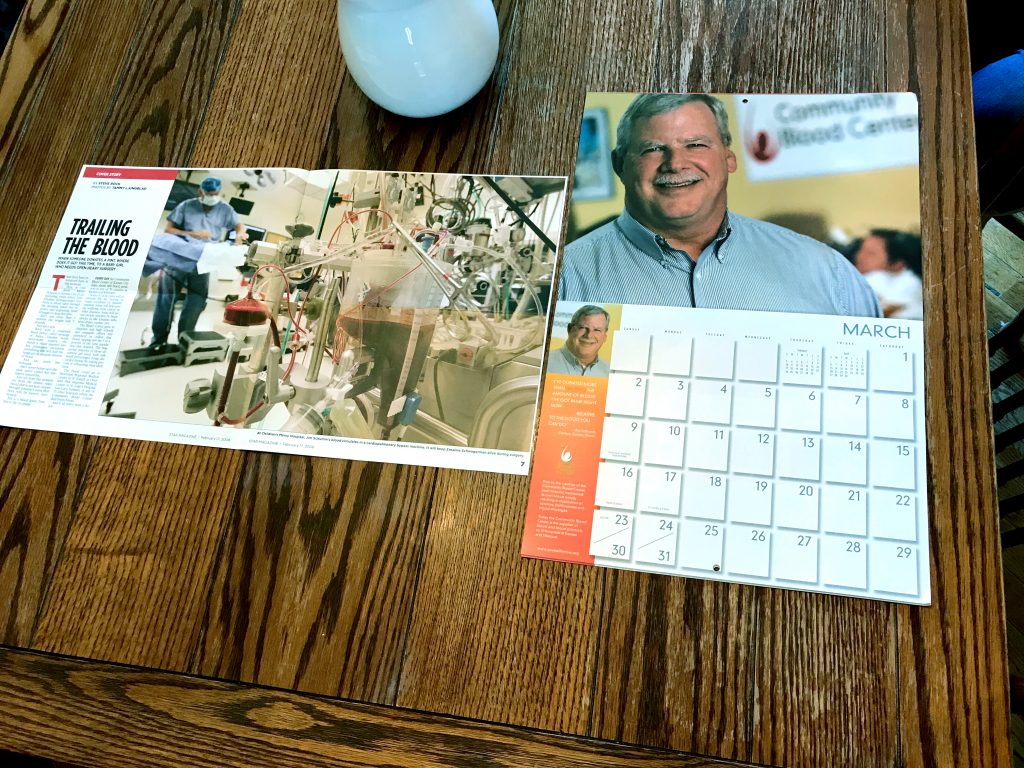

Pictured (right) is Jim Schumm, the blood donor who helped save Emaline’s life when she was a couple months old. An article in The Kansas City Star (left) highlighted how Schumm’s blood was instrumental in keeping Emaline alive during her operation. The Schwagermans have stayed in contact with Schumm the past 10 years and have planned a reunion with him to commemorate the surgery and his donation.

Today, Emaline’s heart is relatively healthy. “She’s doing pretty well,” says Bill as he glances at Emaline. She sits next to him at their kitchen table and plays a game on his phone. “We’re talking about your heart,” Bill tells her. Emaline rolls her eyes in comical exaggeration and returns to her game. Her eye roll says she has heard this story before.

“She will have one more surgery,” says Cindy. “She will have her pulmonary valve replaced and a kink in her pulmonary artery will be corrected. The goal is to get her to adulthood so they can put an adult size pulmonary valve in and be done. No more surgeries.” The tone of Cindy’s voice conveys the hope of not dealing with this condition that has been such a big part of Emaline’s life for the past 10 years.

Struggles and learning experiences

But Emaline’s other condition, Down syndrome, is not going to lessen or go away. “It has completely changed our plans for how we were going to do things,” says Cindy. “We were going to homeschool her or put her in our Adventist school. But it’s like, ‘Okay, she has a cognitive disability. What are we going to do?’ We were getting bombarded with information about early interventions telling us we needed to get her in a center so she can work on her speech, and telling us about occupational and physical therapy.”

Despite feeling overwhelmed, Bill and Cindy were able to get Emaline into the Lee Ann Britain Infant Development Center, an outreach program at Shawnee Mission Health for children with special needs. “God opened the door,” says Cindy. “Our pediatrician and some people in the NICU told us we needed to get our name on the list because there was at least a six-month waiting list, but we didn’t have any trouble getting in.”

The Lee Ann Britain Infant Development Center is located in Shawnee, Kansas, approximately an hour drive from the Schwagermans’ home in Kingsville, Missouri. This drive became too much of an expense, so after two years they decided to stop going. They then discovered that one of the local schools in their area has a special education preschool, where she ended up spending about a year and a half. “She did really well in that,” says Cindy, “but then it was time for kindergarten.”

They weren’t sure if they had the skills to homeschool her, and the Adventist school didn’t have the resources to take her. “She was very high energy. It was almost a full-time job just getting her to stay focused on activities, so we put her in the public school system, and praise the Lord they had a fantastic special education program,” explains Cindy. “The kindergarten teacher was a wonderful teacher and she knew exactly how to incorporate Emaline into the classroom.” Emaline stayed in kindergarten for two years to allow her to more fully develop.

Emaline’s experience changed, though, when she entered first grade. “The first grade teacher just didn’t know how to integrate her into the class, so the whole year was a struggle,” says Cindy. Bill and Cindy didn’t feel like they knew what she was doing or learning, and they had the sense she was just being pushed aside—left alone to do her own thing.

By second grade, the students began to ignore Emaline more and more as they developed faster than she did. Her classmates could tell she was not learning as quickly as they were. “It was becoming obvious she was much farther behind her classmates. They weren’t outright bullying her—they were just kind of ignoring her,” says Cindy. Emaline also began to notice she was being left out of her classmates’ activities, making her like school less and less.

Bill and Cindy reluctantly chose to not re-enroll her in the public school, deciding instead to homeschool her. “It has been a learning experience for her and me,” says Cindy. “Bill and I have advanced degrees. We should be intelligent enough to do it. The question is ‘Do I have the stamina to deal with this every day without getting a break?’”

Emaline reads from her book of Bible verses. She is now able to read at a low first grade, high kindergarten level.

Emaline sits at the table and flips through her book of Bible verses. “No, I don’t want to read that one,” Emaline says as she shakes her head and flips to another page. “That’s the one!” she points. “Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy,” Emaline reads. “Six days you shall labor…” she continues reading, holding her book proudly in front of her. Emaline can now read at about a high kindergarten, low first grade level, and her parents don’t believe she would be reading this well if she had stayed in the public school.

“She misses her friends, though,” says Cindy. “She misses that social interaction with the other students. She misses the choir and getting to do the musical performances.” Bill and Cindy hope that Emaline’s story can bring awareness of the struggle that exists for parents of children with Down syndrome in Adventist or Christian homes. They would like Emaline and other children like her to have a certain amount of interaction and experiences within the Adventist school system, so that what parents are trying to teach at home can be reinforced.

“…Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and hallowed it. Exodus 20:11,” Emaline finishes reading. “I read that good!” she exclaims.

“She couldn’t read at all a year ago,” says Bill. Teaching her at home has been challenging and tiring, but they feel it is their best option.

“So far it’s working okay,” says Cindy. “But we’d sure like to see her have the opportunity to be part of the Adventist school system at some point.”

We’d just like to give her that experience

It is not for lack of willingness that Emaline is not part of the Adventist school system. Bill and Cindy simply feel there is no place that is prepared to take her. “In regards to Adventist education,” says Bill, “we’ve been willing to move since we had her wherever she can get the best education and social life, but there’s nowhere to go.”

“We’d just like to give her that experience of interacting with other Adventist students and the spiritual growth that comes from it,” adds Cindy. But for now, homeschool is where they believe her needs are being best met.

It has been a blessing. It’s forced us to our knees at times and it has made me face some things in my own heart I wasn’t aware of.

Emaline Schwagerman’s energy will wear you out, but it will also encourage you to see her struggle and the struggle of others like her. Her energy shows how well she is doing, despite everything that holds her back. She is happy, friendly and active. Emaline is involved in the Down Syndrome Guild of Greater Kansas City and other local groups for children with learning disabilities. She also attends several camps in Missouri for children with Down syndrome. Her energy clearly shows her need to be with others her age who can teach her, befriend her and guide her in a Christian perspective – her need to be involved in activities with other Adventist children and benefit from their influence.

Despite the challenges, surprises and struggles, Bill and Cindy say their experience has made them grow in ways that never would have happened if Emaline had been born healthy. “It has been a blessing. It’s forced us to our knees at times and it has made me face some things in my own heart I wasn’t aware of,” says Cindy.

“It’s been quite a journey,” adds Bill, “and we’ve grown a lot from it. If everything had gone according to plan, we would be different people.”

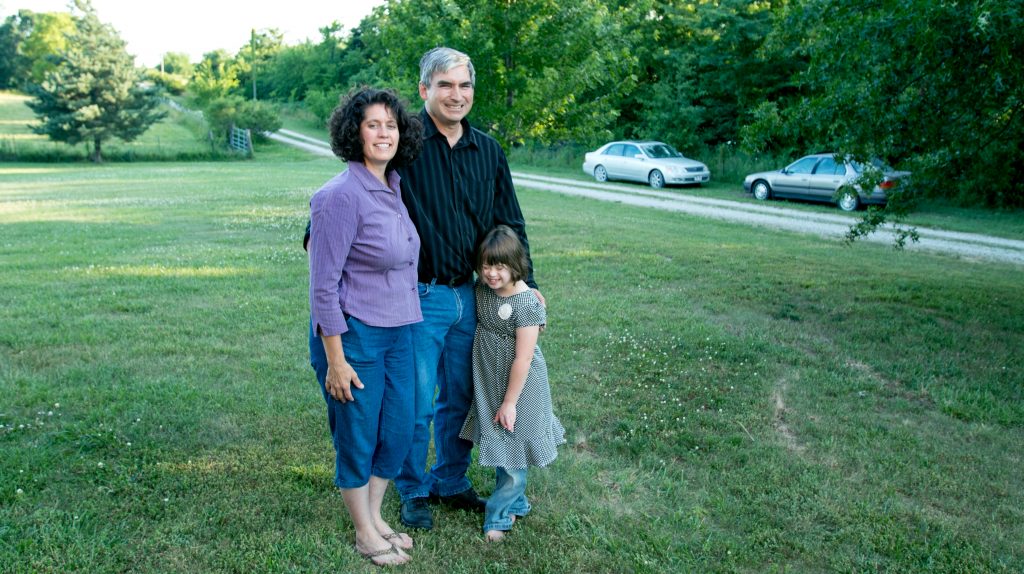

Emaline Schwagerman with her parents, Cindy and Bill, at their home in Kingsville, Missouri