I should have seen it. Matthew tried to tell us. My daughter pointed the way. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me begin at the beginning.

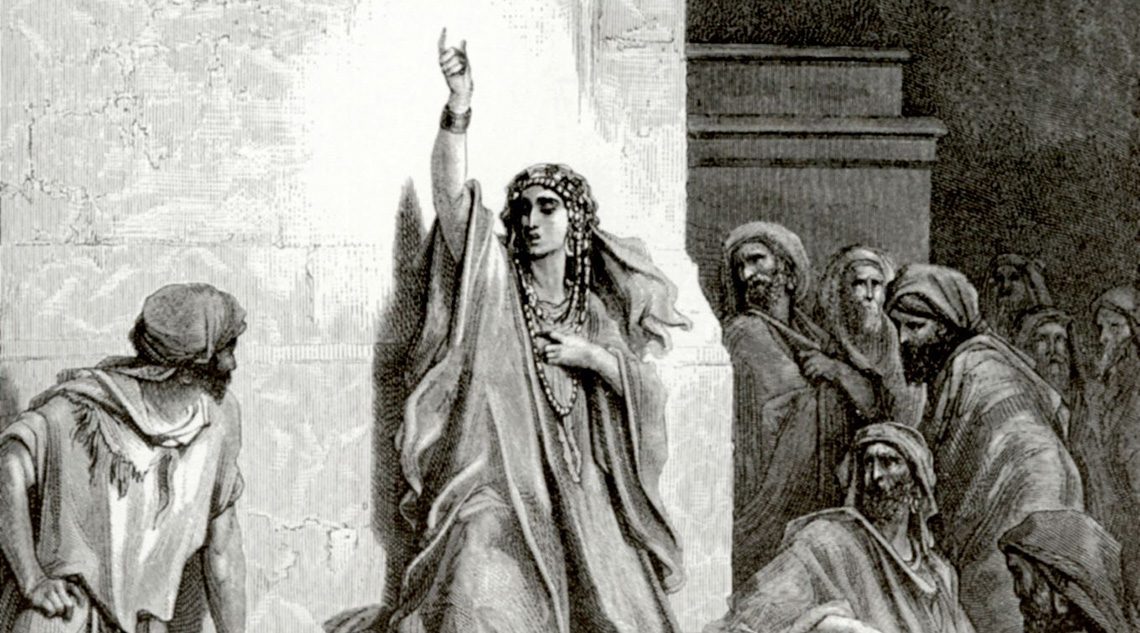

The New Testament begins with the genealogy of Jesus, but it’s a singular genealogy because it includes four women. And not just any women. Matthew does not include Sarah, Abraham’s wife; nor did he include any of the patriarchs’ wives. He does not include Eve, for his genealogy only goes back to Abraham. No, he does not include any of these obvious candidates. Instead, he includes four women with “interesting” back stories.

Matthew includes in Jesus’ genealogy four women with potentially scandalous stories, women with questionable connections. Why?

First, in this genealogy of the Messiah, he includes Tamar. Even in our day, when sexual matters are discussed quite openly, the story of Tamar gives us pause. It certainly made Matthew’s audience a little uncomfortable.

But then he follows up with Rahab, who saved the spies the visited Jericho. When we tell the story to children, we say that Rahab was an innkeeper. But the context and vocabulary in the book of Joshua are clear: Rahab was not just an innkeeper. More discomfort.

As if that weren’t enough, Matthew then mentions Ruth. Now, we finally come to a story with which most of us are comfortable. Partially comfortable that is, because there are parts of the story that we toned down a bit, and partially because we forget the strong prohibition the Jews had against marrying foreigners, especially those from Moab. There are several reasons for this discomfort with Moab, and quite deserved. So now we have three women, each one of them with serious questions about why they were allowed to marry into Israel or, in Tamar’s case, to bear a child who would become an ancestor of royalty. But Matthew is not through shocking us.

It would be difficult to imagine a more scandalous woman than Bathsheba. The story of David and Bathsheba reads like a soap opera. Adultery, betrayal, conspiracy, murder — and that’s just the beginning.

So the question becomes why? Why did Matthew insist on including these women? Why does he insist on focusing our attention on these four difficult situations? Aside from being ancestors of Jesus, what do these four women have in common? After all, in 42 generations, there had to be 42 wives and mothers. Yet only these four are named.

When we look at them, we see they come from completely different backgrounds. Three are gentiles. Three are widows—although one became a widow only after committing adultery. One was an adulteress, another a prostitute, and yet another pretended to be a prostitute. Indeed, that is how she became part of this genealogy. How did such a varied group of women all become ancestors of Solomon—(not of David, since Bathsheba married him)—and of Christ?

Clearly, these were not ordinary women. They did not fit the image of the “perfect woman.” They were not the timid little “fruitful vine in the corner of the house,” the Psalmist’s idea of a good spouse. They had little in common with the “ideal woman” pictured in Proverbs 31. But they did share one crucial characteristic with that woman—initiative. Not one of those women would have been ancestors of Christ if they had not taken initiative, if they had not acted—often contrary to male desires and expectations.

Women who seized the initiative, who did not wait for male permission, did not accept their designated role, honored–by God, since only He could do it–by being included in the Messianic line. This insight reminded me of something my older daughter had said some years ago. Whenever women appealed their case directly to God, she said, He always ruled in their favor.

At first blush, I could think of no examples that contradicted what she had said, and several that confirmed it. But long study in the Bible has taught me to be cautious. The Bible is a complex book, and God in His revelation of His will and His being often surprises us and confounds our expectations. So I’ve learned to be thorough before coming to a conclusion. This series is the product of several years of study into the question.

I did not attempt a study of all the women in the Bible, not even all the good ones. The psalmist described a wife as being “a fruitful vine in the corner of the house.” As positive as that role may be, that was not the type of women I was looking for. After all, society and the church have no problem with women who “know their place.” Biblical approval of the “little woman,” faithfully tending “Kinder, küche, kirche,” is not in question.

I wanted to see how God reacted to women who did not wait for a man’s permission or approval before acting, but who seized the opportunity to act, women who, as Robert Alter described them, were “not content with a vegetative existence in the corner of the house but, when thwarted by the male world or when they find it lacking in moral insight or practical initiative, do not hesitate to take their destiny, or the nation’s, into their own hands.”

So I assembled a list, and eventually came up with 15. Fifteen women who seized the initiative, who often defied convention. I wanted to see how God reacted to them.

What I found at first surprised me, and then as I studied more deeply, it inspired and astonished me. What astonished me was how much I had missed, how little I had understood these tales. Far from echoing the low regard for women in their culture, the biblical writers repeatedly portrayed woman as “a daunting adversary or worthy partner, quite man’s equal in a moral or psychological perspective, capable of exerting just as much power as he through her intelligent resourcefulness.”

Understand, it was not the musings of some feminist theologian wanting to change all the male pronouns concerning God into female ones that influenced me, nor the fashionable theology of the postmodern era. It was the craftsmanship and content of the stories themselves. What I found amazed and inspired me. And it is these stories I will explore in this series of blog posts.

Read other posts in the “Matriarchs and Prophets” series.

—

Personal note: I’ve been absent from blogging for a while. That’s because I’ve crashed a car and a hard drive since the end of January. Neither I nor my data was harmed, but each incident provided a series of obstacles I’m still dealing with. Anyway, I’m back, and looking forward to sharing these stories. I will still blog on Adventist identity from time to time, but most of my efforts will be directed at this new series.