The author was inspired, I’m not.

You might think that rule too obvious to need stating but, alas, it is not. Every one of us is tempted to believe our understanding of a text to be the only possible one–but rarely is that true. And it can be tempting to confuse our understanding of a text with the text itself. We feel justified in declaring the absolute meaning of a text, when we should make explicit that this is our understanding of the text.

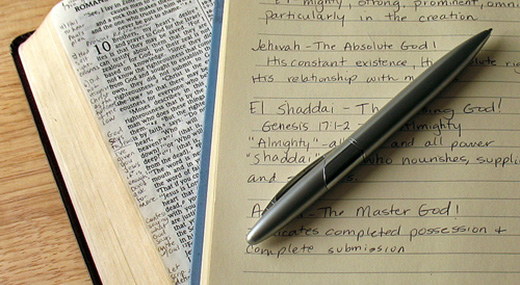

I don’t want to go into a detailed discussion of inspiration, only to say this: Theologians differentiate between inspiration, where God “moves a prophet to declare His will to His people,” and illumination, where the Holy Spirit enlightens their understanding of God’s will for them personally. Those definitions are indicative, not precise or exhaustive.

There are several corollaries to this rule about the author’s inspiration:

- I may not impose my meaning upon the text.

- He said what he said; I may not change it to make it easier to understand.

- I may not tell him what he should have said.

Just because I “need” the text to say or not say something does not mean I am free to bend it to my will. One of the great values of having a text, a written record, is that it does not change. If we change it to fit our needs, we have not only dishonored the original, we have forfeited its authority. Because the Bible was written so long ago, and because word-for-word translation is impossible in a practical sense, we will continue to find some texts difficult to understand.

For example, the question of what was “nailed to the cross” in Colossians 2: Some have interpreted that to be the law, as in the Ten Commandments. Others have countered that it was the ceremonial law–the law of Leviticus, for example, but not the Ten Commandments.

Instead of simply declaring it to be one or the other, let’s find out. You don’t have to know Greek to find out what words were used. You can go to one of the online interlinear versions and find the Greek phrase: cheirographon tois dogmasin.

Simply type that into your search bar, and you’ll find numerous explanations of the term. You’ll find that it is used only once in the Bible, and that the literal meaning is “handwriting of requirements,” but a more specific meaning is a “bill of debts.” Like many words in any language, this phrase has a range of possible meanings.

By typing Colossians 2:14 into the search bar on your browser, you can compare multiple translations of the text at Biblehub.com Here are several:

NIV: having canceled the charge of our legal indebtedness, which stood against us and condemned us; he has taken it away, nailing it to the cross.

NASB: having canceled out the certificate of debt consisting of decrees against us, which was hostile to us; and He has taken it out of the way, having nailed it to the cross.

ESV: by canceling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands. This he set aside, nailing it to the cross.

Note the difficulty of understanding the meaning “contrary to us,” “stood against us,” “condemned us.” The one that catches it best, I think, is the Phillips:

Phillips: Christ has utterly wiped out the damning evidence of broken laws and commandments which always hung over our heads, and has completely annulled it by nailing it over his own head on the cross.

You will notice, however, that is a very dynamic translation, since the words “hung over our heads” is not in the Greek, though I think it catches the sense of it best.

So, is it the Ten Commandments, the Levitical law, or what? I think the answer is neither and both. The passage is not concerned with whether any of these laws and regulations were done away with, but that the debt we owed and the guilt we felt for breaking any and all of them was eliminated at the cross. What a wonderful text! You may notice how using it to prove a point about either the Ten Commandments or the Levitical law distorted the meaning of the text.

The biblical authors spared no effort to communicate effectively the will of God as they had received it, and present it in a way which would most impress the heart of the reader. If, then, we treat their work as a collection of disconnected sentences to be reduced to individual phrases or sentences, and then reassembled to suit our transient needs, we do both the human author and the Divine Revealer grave injustice.

Whenever we bring to the Bible rules or paradigms contrary to its own nature and claims, we are not listening to the author. We are assuming that we are the ones who really know what the text means, in effect, that we are inspired. And when we do that, we generally demonstrate that we are neither inspired nor illuminated.