Naomi knew what she was talking about. Boaz had gone to the city with a clear purpose in mind: secure for himself the land of Naomi and the hand of Ruth.

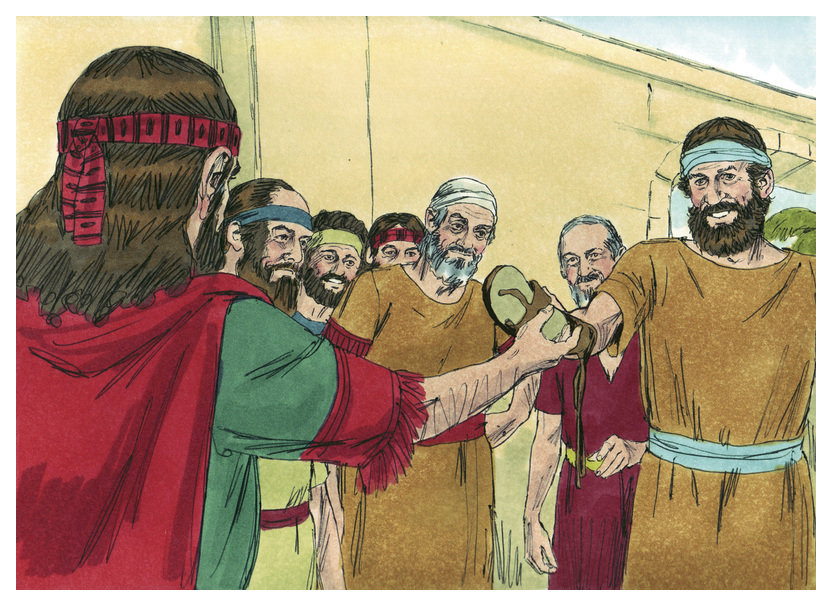

Now Boaz went up to the gate, and sat down there. Behold, the near kinsman of whom Boaz spoke came by. He said to him, “Come over here, friend, and sit down!” He turned aside, and sat down.

He took ten men of the elders of the city, and said, “Sit down here,” and they sat down.

The ancient reader recognizes this scene immediately. It’s like the opening of Perry Mason or Matlock, or a scene from Law & Order: we see a courtroom, a judge upon the bench, the jury waiting. A legal proceeding is about to begin; justice will be dispensed. In the ancient world, wise men gathered at the city gate, and individuals brought here their petitions to be decided, their disputes settled. Boaz recognizes a timeless truth that sometimes we forget: Justice must be done, and must be seen to have been done. For any society to maintain internal order, justice must be done. For that society to also maintain internal peace, justice must be seen to have been done.

Their law requires that a young widow receive the care and support of a husband; justice must be done. But a procedure exists on how this relief is to be provided and who should provide it, and that procedure must be recognized as fairly administered; justice must be seen to have been done. Boaz has determined to satisfy both requirements. He brings the case before his impromptu witnesses—the ten elders.

He said to the near kinsman, “Naomi, who has come back out of the country of Moab, is selling the parcel of land, which was our brother Elimelech’s.

I thought I should tell you, saying, ‘Buy it before those who sit here, and before the elders of my people.’ If you will redeem it, redeem it; but if you will not redeem it, then tell me, that I may know. For there is no one to redeem it besides you; and I am after you.”

The author of this story does not name the near kinsman, thus making clear that he is not a significant player in this narrative. Yes, he has a choice to make—he could be a major character—but not being named forewarns us that he will not be. Note that in this narrative, the “near kinsman” appears in the role of the firstborn, that is, according to birth he is more closely related to Naomi than Boaz and thus receives preference. But as mentioned earlier, in Scripture the firstborn almost never actually benefits from that accident of birth. At first, this looks like an exception (but don’t forget we don’t know his name!). Apparently eager to acquire the land for himself, “He said, ‘I will redeem it.’”

It appears that Naomi’s stratagem and Ruth’s desire—that she marry Boaz—has failed. But, just as Naomi knows Boaz, Boaz knows his unnamed rival, and at this point he mentions the rest of the purchase price:

Then Boaz said, “On the day you buy the field from the hand of Naomi, you must buy it also from Ruth the Moabitess, the wife of the dead, to raise up the name of the dead on his inheritance.”

Here we have a fascinating insight into the whole issue of what we call “levirate marriage”: “You must buy it also,” Boaz says, “from Ruth the Moabitess.” The price of the land, whether in coin, livestock, or other items of value, would go to Elimelech’s widow, Naomi, to support her in her old age. But the existence of a marriageable widow, namely Ruth, meant she also must be compensated. And that price consisted of the requirement to give her a son, “to raise up the name of the dead on his inheritance.”

The near kinsman had already agreed to pay the first price; the second one, however, posed an insurmountable obstacle in his mind.

The near kinsman said, “I can’t redeem it for myself, lest I endanger my own inheritance.

What does he find so daunting about marrying Ruth that it would “endanger” his inheritance? It comes down to this: when a man died, his possessions would be divided by the number of living sons, plus one. The firstborn would then receive two of those portions, “the double portion.” We don’t know how many sons the nearer kinsman had, or if he had any. If he had none, and he married Ruth and she bore him a son first, two portions of his legacy would go to that child, who would be considered Elimelech’s son. If he had no other sons, all of his possessions would go to Ruth’s child. In any case, part of his belongings would go to someone legally recognized as another man’s son. He decided not to take that chance.

We do not know the nearer kinsman, if he had other sons or not, but Boaz did know. And the way Boaz handled the case, first simply mentioning the land, and then the required marriage, with its implications for the man’s legacy, tells us he had a good idea of how the man’s mind worked. The near kinsman jumped at the chance to buy the land, but declined the marriage.

And in so doing, he completes the Firstborn’s Reversal story framework. Like virtually all of the type scenes or story frameworks in the book of Ruth, the author has turned expectations upside down, and with a clever twist. Boaz and the near kinsman are not brothers, but as we noted earlier, “the ‘near kinsman’ appears in the role of the firstborn, that is, according to birth, he is more closely related to Naomi than Boaz, and thus receives preference.”

In previous instances in Scripture, the reversal happened in spite of and contrary to the firstborn’s wishes: Isaac is preferred over his older brother, Ishmael; Jacob steals his brother’s blessing; Reuben loses it by asserting it too soon; and Jacob intentionally confers it on the younger of Joseph’s two sons. Here, with appropriate irony, the near kinsman declines his firstborn privilege.

At this point, this fascinating tale approaches its conclusion. Indeed, the way we usually tell the tale, once Boaz secures the right to marry Ruth, we note that she was the mother of Obed, who himself is grandfather to David who will be king, but we skip over some of the delicious details the author has worked so hard for us to appreciate. We have essentially concluded the Betrothal Narrative, and now the Firstborn’s Reversal, but several other loose ends remain. We turn to those next.